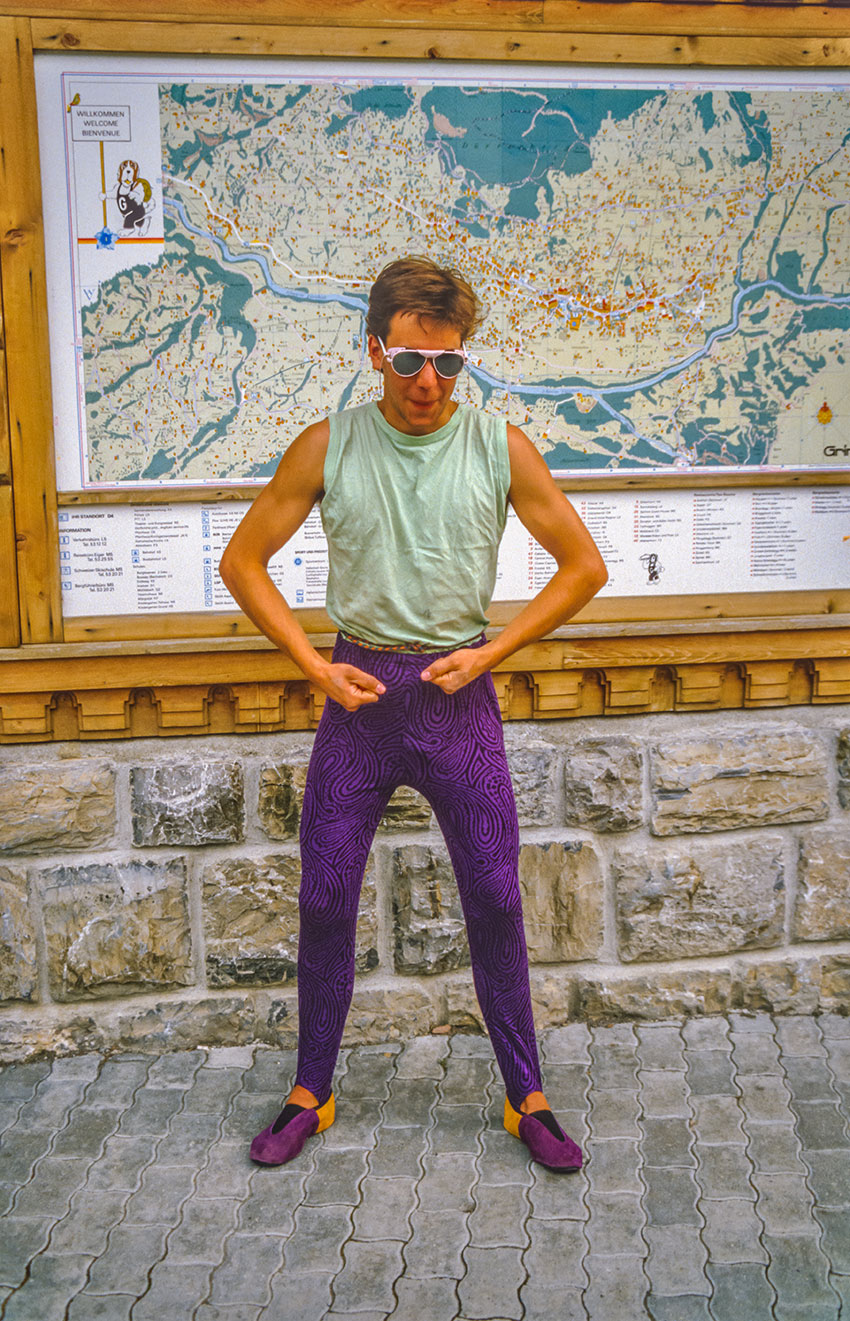

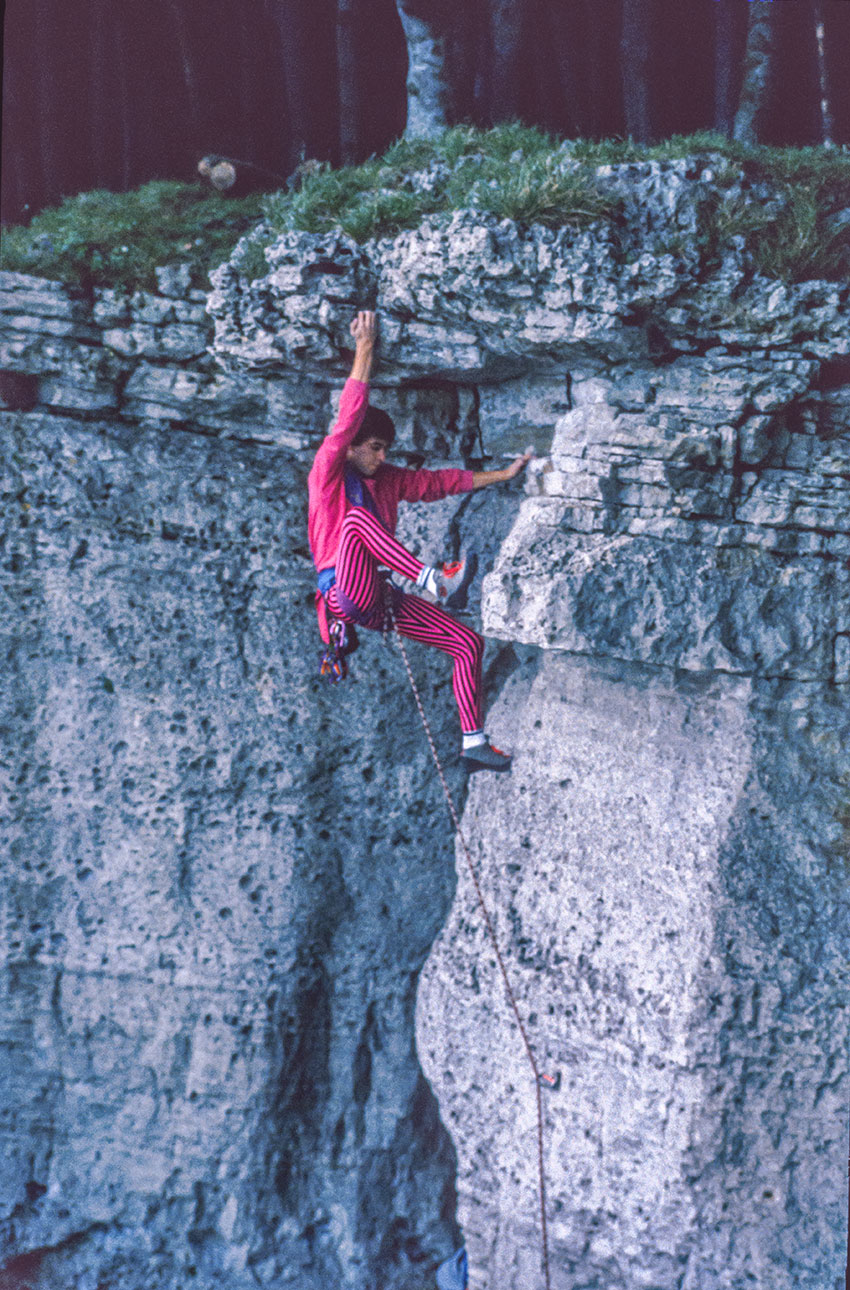

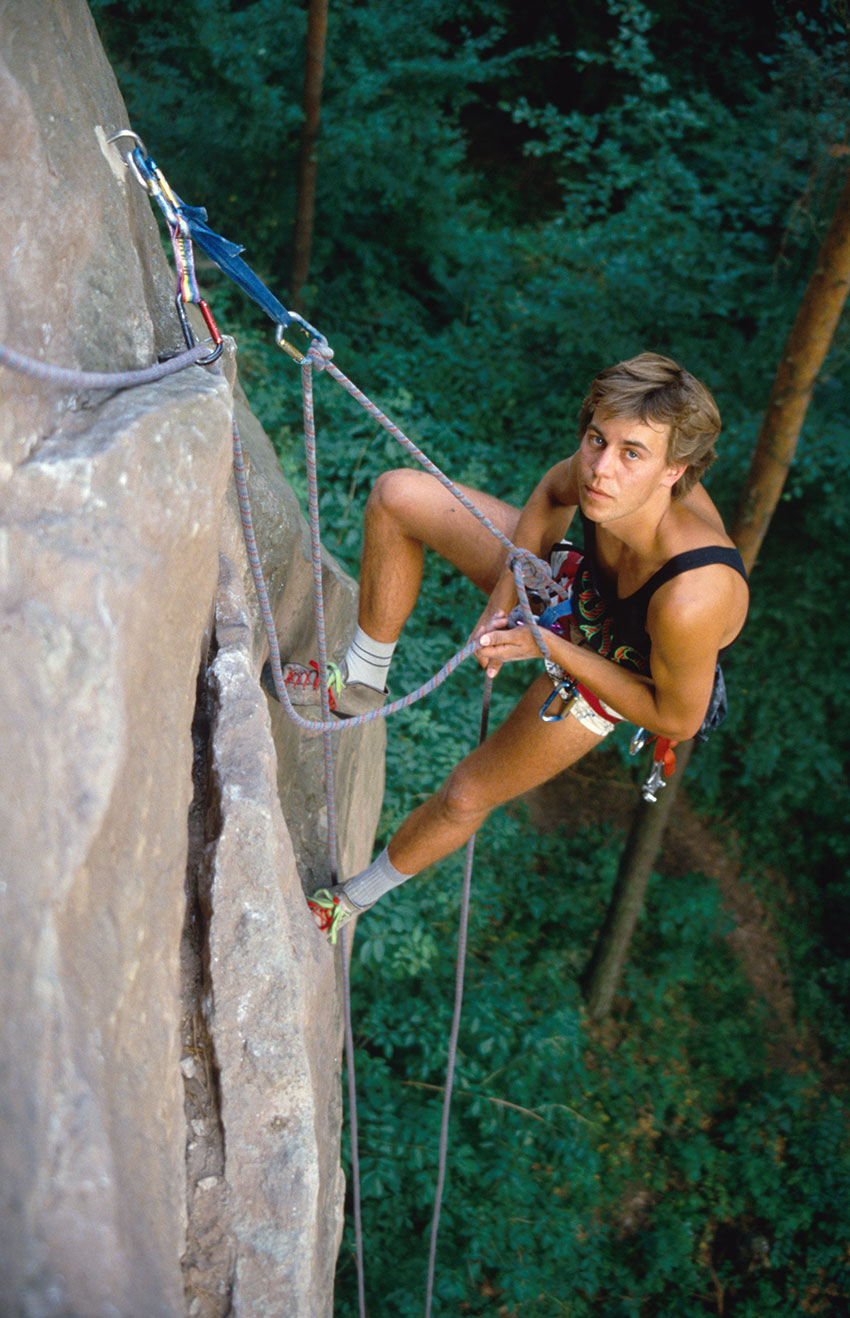

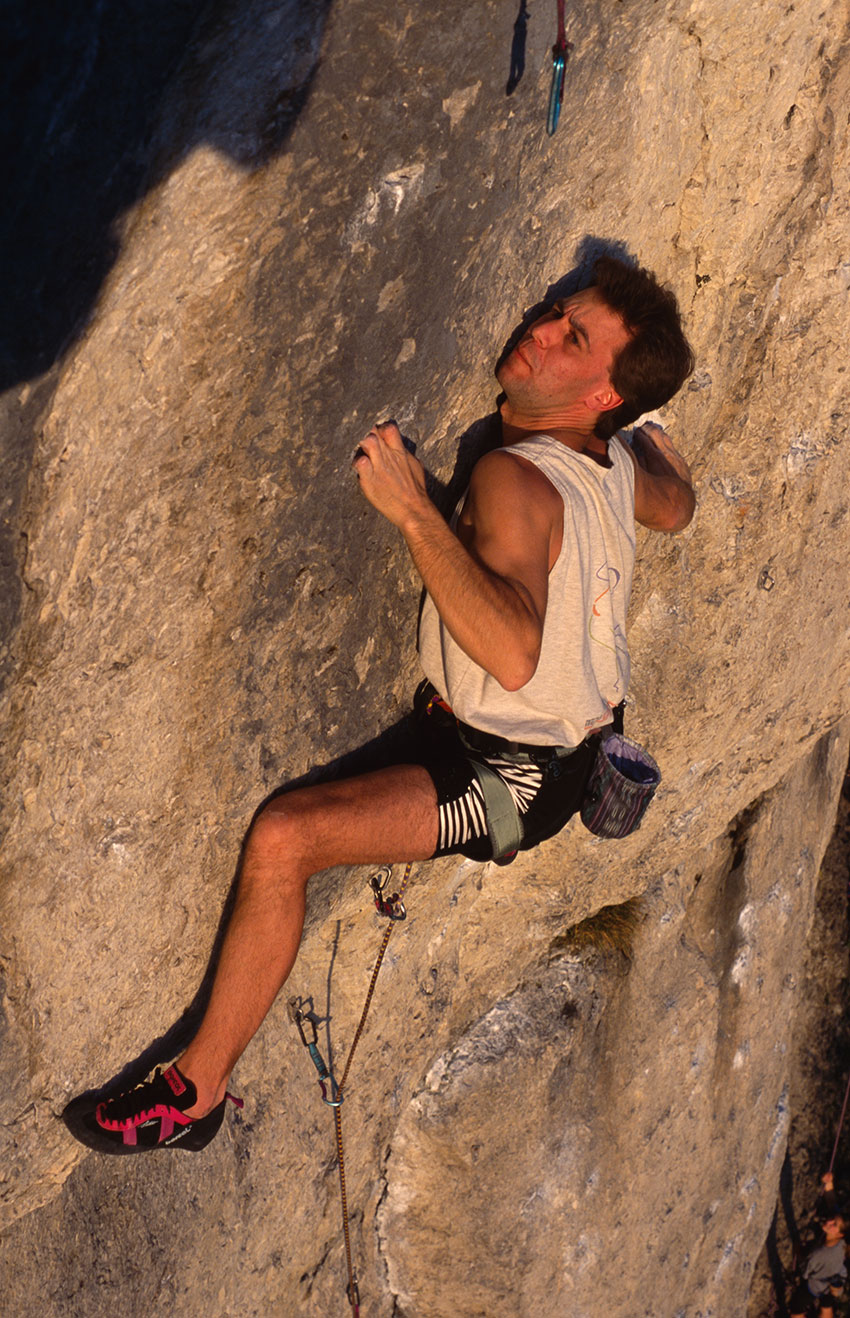

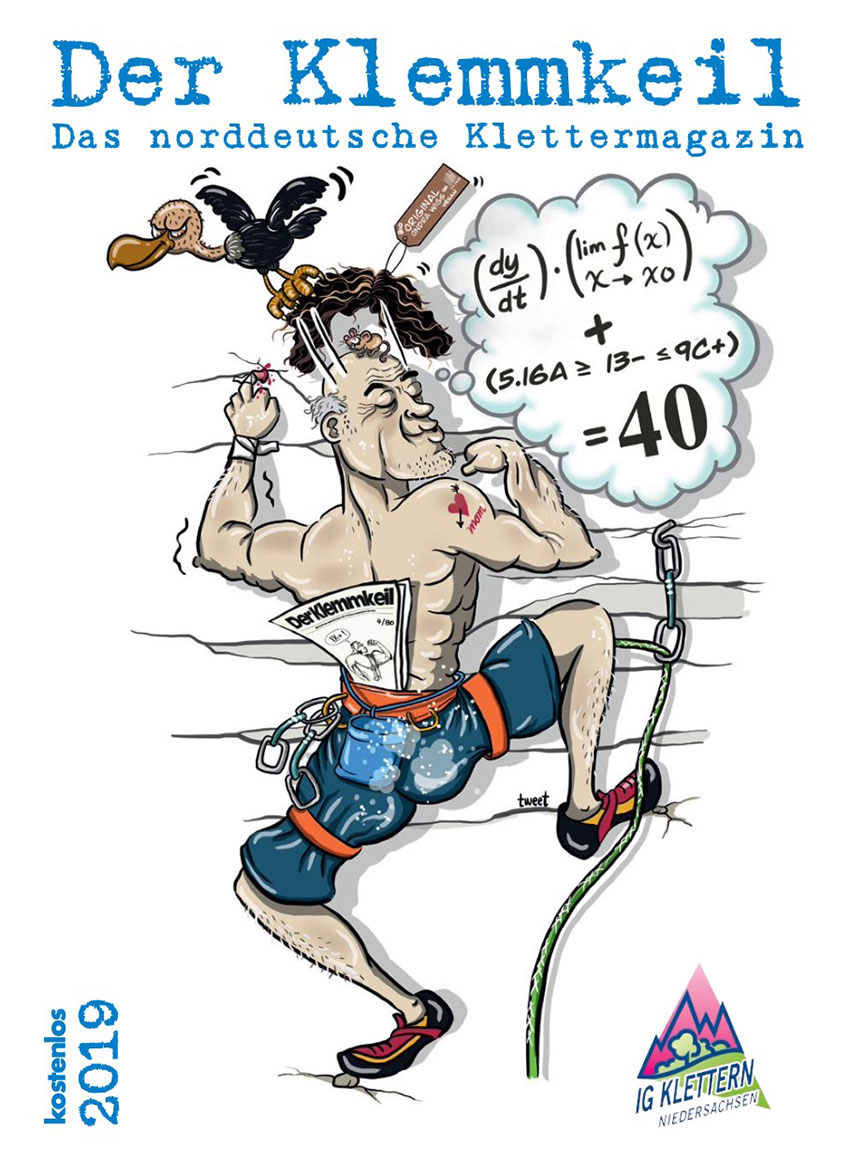

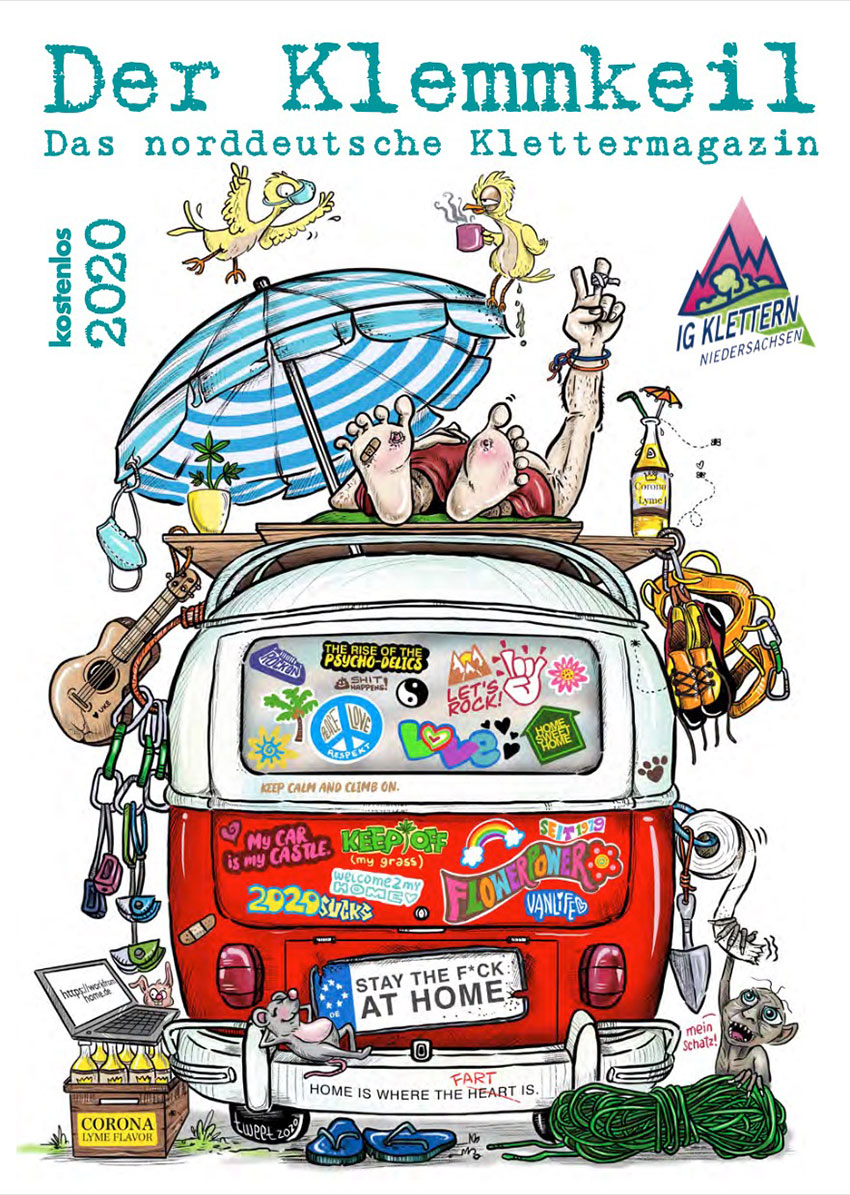

Jürgen: Welcome to the “Frankenjura-Dude-Rockshow”. I would like to welcome a real boy from Hamburg, who found his way to climbing after a canceled diving vacation. We learn why he found school sports to be fairly mediocre, but why climbing in the Weserbergland ignited a fire in him. He was also fascinated by climbing on bridges, which did not go down well with the local police. I am curious to know why a project on the experimental image of man ended with a jump from a bridge and how he discovered his love of photography. He became the strongest climber in Hamburg. Of course, alpine experiences were also needed. The Eiger and the Matterhorn were some of his alpine destinations. The north faces were not safe from him either. Further afield climbing areas in Germany and Europe had to be discovered. Portugal, Frankenjura, Pfalz, all the important areas in France and also Norway. I am curious to find out why Norwegian cowgirls are sometimes melancholy and how this is related to a fantastic first ascent. Slide shows, the ancient predecessors of PowerPoint presentations, gave him the financial opportunity to also gather impressive experiences on the other side of the pond in the United States. He provided readable articles in the legendary “Rotpunkt” magazine, including about his home area with great pictures. But why just one article? Let’s do a whole issue. No sooner said than done. So he got involved in the IG “Klettern Niedersachsen” and, together with the editorial team, turned a loose collection of pages into the ultimate, and only, North German climbing magazine “Der Klemmkeil” as editor. Our picturesque landscape and, of course, the rocks and routes have long since taken a shine to him. And so we find out how the Frankenjura took him hostage. And even his mother asked him, “when will you finally give up”? We welcome an alert, interested mind that consistently pursues its goals in all areas of life. He doesn’t just talk, he follows through on his plans against all odds. He is a motivational wonder, very reflective, passionate, articulate and full of energy like the Duracell bunny. A warm welcome to Mathias Weck. Mathias, greetings.

Mathias: Greetings, Jürgen. Thank you for the invitation.

Jürgen: I’m glad you’re here. That was a brief intro to your climbing career. But where did you actually grow up?

Mathias: I’m from Hamburg. And at this point, thank you very much for your great and inspiring podcasts. I always listen to them on long car rides. I have to say, I’ve listened to them all by now. I’ve taken something from each of them for myself.

Jürgen: Really?

Mathias: Whether it’s Norbert Sandner, who reported on the aging Kurt Albert, who found it uncomfortable to even climb rocks where others were watching him. We all age at some point. My performance curve is also going down steeply. And sometimes you feel ashamed that you might not be able to do one route or another as well as you used to. Or Sebastian Deppe with his really extreme physical limitation, with the jamming even in normal holds and stuff like that. I think you can take something away from every podcast. Thank you very much for that.

Jürgen: That’s great. Thank you, Mathias. How did you get into climbing? How did you grow up there? I mentioned Hamburg before.

Mathias: Exactly. Actually, my parents wanted to go to Sweden on vacation. I had bought diving fins and diving goggles. I wanted to go diving in the lakes there as a 12- or 13-year-old. We’ll come back to that later. Diving caught up with me much later in life. But at that point, it was all canceled. We were told just before we were going to go to the mountains and not to the Swedish lakes.

Jürgen: You actually wanted to go diving?

Mathias: I actually wanted to go diving. Then I said I didn’t feel like going to the mountains. I’d stay at home if necessary. Fortunately, I went with them after all. They went hiking. Somehow I was tempted to fill out stamp books. And to go from hut to hut. Then there was a hiking pin afterwards. I liked that so much that I thought maybe I would continue doing it. Maybe you can collect stamps in the North German lowlands too. Then I ended up with the Alpine Club. I wanted to subscribe to a mountain magazine. The Alpine Club had a section magazine and a magazine from Munich. I think it cost 13 German Marks at the time. That was really cheap. They also had a youth group, which I assumed meant that they all went hiking. Nobody went hiking, they all climbed. Since then, I have been collecting climbing grades rather than stamps.

Jürgen: So it was, so to speak, the way through the DAV, that was actually the gateway to climbing.

Mathias: Yes, exactly. There’s a pretty funny story about that. The first climbing weekend, where I was finally allowed to go out, it was quite an adventure getting there. So we made our own climbing harnesses, a chest harness out of old rope scraps, and sewed it, so to speak. Well, that was all…

Jürgen: You built it yourselves?

Mathias: Yes, exactly. Well, it was knotted, but also sewn. It was exciting, it was a great time with the youth group.

Jürgen: Let me ask you a quick question, I still remember when it was. Was that in the 80s?

Mathias: Yes, that was in the fall of 1980. So that makes it… Yes, it will be 45 years since the first climbing trip in the fall of 2025. And… yes. It rained all weekend. And at the Ith hut, which has an attic, we just slept on sleeping mats back then. But it was the weekend, because it rained so hard, it rained so terribly hard, the whole weekend was not spent climbing, but a so-called Ith Crystal Night took place.

Jürgen: Let me ask you briefly, so it is actually the case that it is not just a story that it rained so much?

Mathias: Yes, unfortunately yes.

Jürgen: Okay. Okay, a Crystal Night, what is that?

Mathias: So, there’s a lot of drinking. At the age of 13, I didn’t have anything to do with that. And then the empty beer bottles are thrown down through the hatch in the floor of the Ith hut’s attic. And then there’s a big clink and a pile of broken glass down there.

Jürgen: Okay, it’s like a wedding eve.

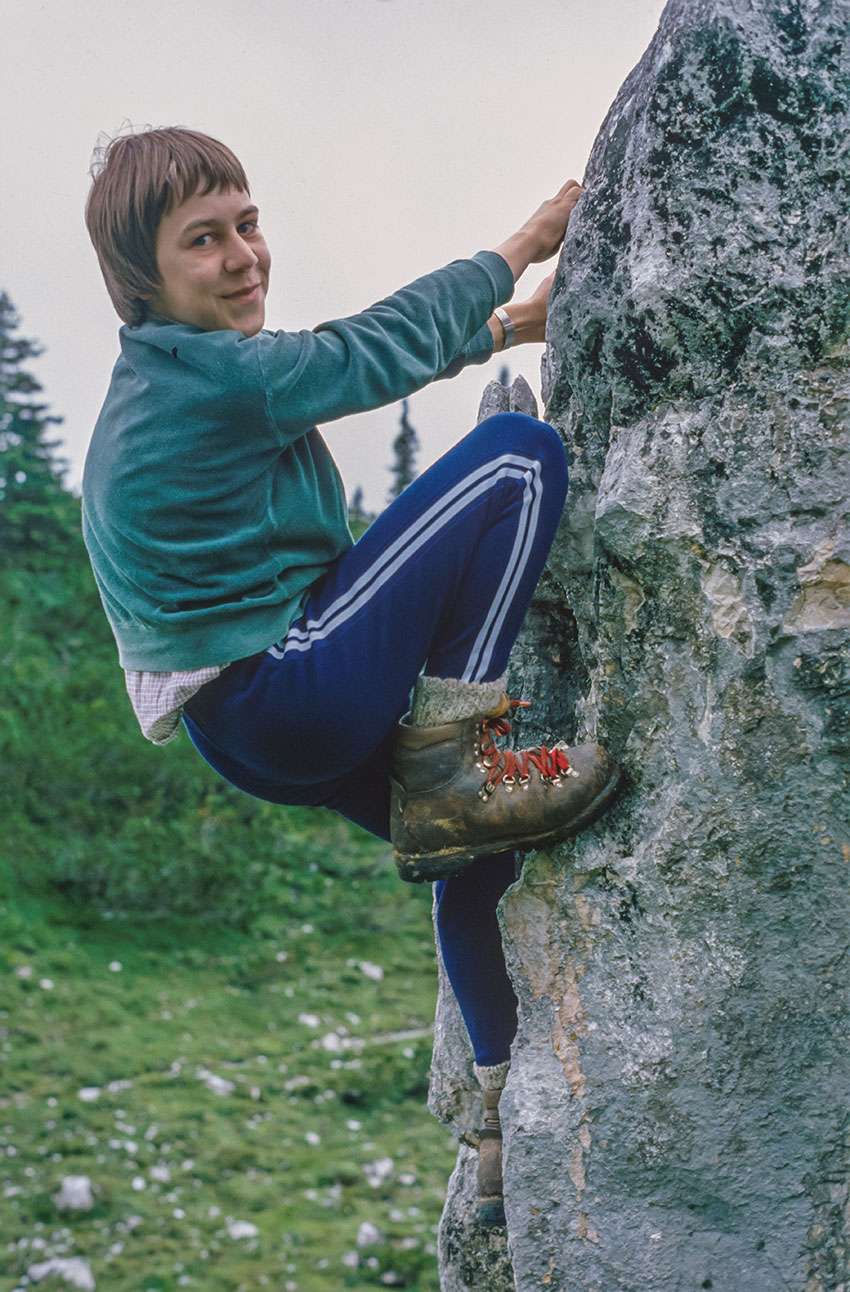

Mathias: Right, exactly. If you have to go to the bathroom at night, you should be careful not to step on the shards. But on Sunday afternoon in the pouring rain, Anke Ruth, thank you, thank you, Anke, if you should see this podcast, you initiated my climbing career back then, and you let me climb the Damenweg, 2-, in the pouring rain. Back then, with thick mountain boots. We even rappelled from the top. And yes, that somehow… triggered everything for me immediately. And I was hooked. And at Easter 1981, it really took off. That was the first real trip with the DAV youth group. And yes, that… gave me a lot of pleasure. And yes, slowly but surely, I made my way up the climbing grade scale.

Jürgen: Okay. I said earlier in the intro that school sports were so-so. Were you just really into sports in school? And that’s why climbing came about as a logical sporting development, so to speak?

Mathias: Not at all. I was always the last to be chosen in sports. So really tragic for a boy. And you still get Mathias. Oh no, does that have to be?

Jürgen: Can’t you have him?

Mathias: Yes, exactly.

Jürgen: Okay.

Mathias: And I suffered terribly from that. So there were also three or four classmates who often beat me up in the schoolyard. And so those were really not pleasant memories. And then climbing suddenly flipped a switch.

Jürgen: It’s also about self-confidence in what you can actually achieve.

Mathias: Yes, exactly. And it wasn’t that I was competing with others, but rather that I was competing with myself. And it’s the same for anyone who manages a route somewhere. I do the same when I take friends out who have never climbed before to go and climb with me. They ask if they can do it. And I say, yes, you’ll feel a sense of achievement right away, whether it’s a two, three, four or five-grade route. If you manage to get up there, you’ll feel joy. And that’s how it was for me, too. And yes, if you climb a lot, then at some point the strength comes all by itself. And then at some point in school sports, they said we had to do pull-ups again. And I think the best in the class could do seven pull-ups. And then I did 15 pull-ups.

Jürgen: Oh, but then you’re on top of the world.

Mathias: Yes, exactly. But it was actually impossible that the weakling Mathias could somehow do 15 pull-ups. So there was a discussion about whether I did them too quickly.

Jürgen: Oh.

Mathias: Yes, I think, in contrast to my classmates, we will have our 40th anniversary this year, I think, but at the last meeting it was already the case, that only few are still active in sports. So, climbing keeps you young. And as we just saw in the last interview with Irmgard Braun, who is still a great role model for me.

Jürgen: Awesome, great. At 72 years old, amazing.

Mathias: Yes, impressive too. I asked Irmgard recently, “Tell me, Irmgard, doesn’t everything hurt for you too?” I mean, I’m 58 now and it hurts all over somehow. And she says, “No, nothing hurts for me.”

Jürgen: Okay. – That gives you hope now, right?

Mathias: Yes.

Jürgen: She also said a nice sentence. “Stay or become flexible.” So, really the invitation, so to speak, to incorporate this flexibility into your training as well, of course. Yes, and then it was practically, well, Anke took you. You just told us about the climb „Damenweg“ (Ladies’ Way) with shining eyes, which is nice, because it’s just away from “climbing only starts at the seventh grade or the eighth” or whatever it’s supposed to be.

Mathias: Yes, exactly.

Jürgen: But while you were climbing, you were also in the Donautal.

Mathias: Yes.

Jürgen: Yes, and I think something relatively unpleasant happened there. An accident.

Mathias: Yes, exactly. Well, maybe I should add that I went to a Waldorf school. That meant that there was always school on Saturdays. But my parents somehow always supported my climbing from the very beginning. That said, they even picked me up at school on Saturday afternoons and then dropped me off at a the highway rest area so that I could hitchhike to the Weserbergland as quickly as possible on Saturday afternoons.

Jürgen: Then you were picked up at the rest area and on you went.

Mathias: At the beginning, they were skeptical about me hitchhiking, but then they accepted it. And so, hitchhiking was just part of the program. For those who don’t know it, hitchhiking is when you stick your thumb out and then a car stops.

Jürgen: This is actually something that needs more explaining. You say it was more natural back then, but how do I get there? And then, sticking your finger out and hitchhiking was the solution, it has decreased quite a bit. You were always relatively quick…

Mathias: Yes, that always worked. Saturday afternoon I was on the Ith. And it was the same in the Donautal. And since I didn’t have a climbing buddy at the time, I recruited two girls and a guy from school. And then we hitchhiked to the Donautal and set up camp in… I don’t remember the name of the hut anymore. Well, it was right below the rock there. And yes, in the afternoon we did the first route there, kind of a fourth-grade climb. Wolfgang, the guy, had a leather floppy hat on. And it was blown off the rock. And I thought, okay, maybe it’s either down in the forest or maybe somehow on the ledge. And then I climbed ten meters up. Grassy, brittle, mossy terrain. The hat was not on the ledge. At that moment, my friends were already shouting that they had found the hat. I probably slipped somehow while climbing down, or something broke. In any case, I fell ten meters to the ground. And it wasn’t like the inner movie was playing in my mind’s eye. But it was definitely pretty life-threatening. I was lying there in the forest gasping for air. It was „only“ a pneumothorax, that is, the negative pressure from the lung collapses. And so you can’t breathe anymore.

Jürgen: And that’s pretty dramatic.

Mathias: Exactly. The doctor who came and felt the pulse said everything was fine. Luckily, the friends insisted and called the ambulance after all. And after one night in the emergency room, they decided that everything was fine, transferred me to a normal room, only to realize the next day that I would have to undergo surgery. So then I was somehow hooked up to this machine for ten days, which then artificially restored the vacuum of the lung chamber, so that it could heal. A funny anecdote on the side. When the tube was to be removed, I asked the doctor, “Doesn’t that hurt?” “No, you just have to cough a little, then I’ll take out the tube, it won’t hurt at all.” He pulled and I screamed like a banshee, and he said, “Oh, it’s still sewn on.”

Jürgen: Oh God. (laughs)

Mathias: But nevertheless, well, I was already reading climbing magazines in the hospital again. And I am extremely grateful to my parents for that, too. Because they visited me in the hospital. It’s hard for parents to get a call that their son is in intensive care.

Jürgen: Because, after all, climbing was still considered dangerous.

Mathias: Right, exactly. And, yes, well, they kept bringing me climbing magazines to the hospital and said, yes, we know this was bad for us, but we know that climbing means everything for you and you will continue to do it. So, here, just read it.

Jürgen: Your parents already sensed that? – Yes. Okay.

Mathias: Yes, they have always been supportive to me. And left me a lot of freedom. This started already in school. At the Waldorf School, I had opted out of the second foreign language and didn’t want to do my A-levels. I was a mediocre student. And then suddenly, in the twelfth grade, there was a real rocket ignition and in the final certificate, I somehow had a perfect average. And I said I wanted to do my A-levels after all. Then my parents said, okay, we’ll give you the opportunity to do that, too. Before that, they had also said, we’ll let you do what you want, you don’t have to graduate. Then I went to the business high school and graduated.

Jürgen: It’s a plea for it and a trust from the parents, isn’t it? That you just really say, let it be, because he’ll find it on his own. In this case, it worked out great.

Mathias: Yes, well, I can advise any parent who somehow think they have to be a helicopter mom or dad. Guys, let the kids, give them free rein. They’ll develop. The more freedom you give them, sure, they’ll fall on their faces, something will happen to them. But in the long run, it’s certainly the better way for the children to be independent.

Jürgen: You said they also learn something from it. Now back then you were looking for the hat, so to speak, from Wolfgang. What did you learn from it? What do you change so that something like that doesn’t happen anymore?

Mathias: Well, solo climbing has never really been mine. Sure, I actually tried it somewhere too. It was also a thing of the time.

Jürgen: Yes, it was totally en vogue in the 80s. Everyone had to try it at least once, or something like that.

Mathias: And it was just the highest and purest, the highest and purest form of climbing. But it never really became mine. Maybe it also has to do with the early days.

Jürgen: I think you were also… You also tried other things. There were bridges like that back then, for example. The Kine-Swing, for example. Or the Calpe swing.

Mathias: Exactly. That was something that was also a bit the spirit of the time, at least a bit of a trend. That you attached a rope to a bridge, so to speak.

Jürgen: And, yes, explain, what was done there?

Mathias: Exactly. The famous Kine-swing is two highway bridges. Or two road bridges, which… I think they are near Geneva down below, so in the direction of the south of France, 50 meters apart. They stretched a rope between the bridges, tied it on one side, jumped and then had a giant swing of almost 100 meters. And there was something like that in Spain, too. So I thought, maybe we could do that too. Then we threw a backpack and it went damn close to the bridge pier or the rock face. And I called it off and didn’t do it. I also liked reading accident reports and learning from other people’s mistakes. I think that’s the nice thing about having a long climbing life: you can look back on all the crazy adventures. You can be happy that you’re still alive at all. But you’re only alive if you know when to call it off at the right time. And yes, I think I was very lucky back then. That’s also the nice thing about the podcast here. Of course, you research beforehand what you have already experienced. And to be able to look back on this long climbing life and to dig up these memories again, that’s something beautiful. And it’s a shame if you can’t do that because then maybe you died very young.

Jürgen: In that case, you decided that the swing was not that important. That means you threw the backpack down as a test and said, no, it’s just too risky. Did the Donautal play a role in this? Do you think that something has changed in terms of safety?

Mathias: I think that with the Donautal, it was still too early in life. It was quickly forgotten, I never really was fearful in climbing. I think fear was never really a part of climbing for me.

Jürgen: Okay. – Mhm. Okay. There was also something after your school days, which you just mentioned. Namely, the community / alternative service. You did that too. I think we have to explain in 2025 what community service is. But I’ll give you a keyword. A tour called “Dämmerung” or “Crepuscale”. What role does that play? “Dämmerung” or “Crepuscale”. What does that have to do with your community service?

Mathias: Yes. (laughs) Well, community service was kind of a part in the family, because my father, in, well, quite early years, so, early years, so… in the 60s, I was born in 1967, already refused to perform military service. And that was after he had actually already done his military service. That made a big impression on me, because I think he would have had to wait another two weeks before he was done with it. But he said no, he wanted to make a statement. And that was an absolute no-go at the time. It also blew up in his professional face a bit. He wanted to…

Jürgen: Really?

Mathias: Yes, to become a flight engineer for Lufthansa. And then they said, what will you do if we have to call you up in case of war? Unfortunately, we can’t take you then.

Jürgen: Really? – Yes. Okay, that really had an impact on his career.

Mathias: Exactly, yes. And I think it was good for us children because he was always around and not gone for work trips. And, yes, but it definitely made an impression on me somehow. And of course I was able to refer to it then, well, because my father refused. But in my time, you also had to write a long essay explaining why you didn’t want to do military service. I did community service instead and never regretted it. It was a really very enriching time. I worked in the mobile social assistance service, taking care of older and disabled people. I often did things that went above and beyond what I was required to do. I had an older lady who was mentally still completely alert, but almost blind. I went swimming with her.

Jürgen: Oh, nice.

Mathias: That was actually part of the program, it was official. What wasn’t part of the program was going to a concert with her in the evening. But she said, “Look, next week, you’re welcome to take a day off, you were at the concert with me.” I took advantage of that, during that time I had a girlfriend in Paris and then I went to Fontainebleau for a long weekend to boulder every now and then.

Jürgen: Perfect.

Mathias: So, give and take, I understood that relatively quickly, that you have to give something before you can take.

Jürgen: And maybe not always immediately calculate what is sometimes in time, because you also said, come on, then I’ll go to the theater in the evening, even though that wasn’t your job. I think you also enjoyed that, that’s how I know you now, right?

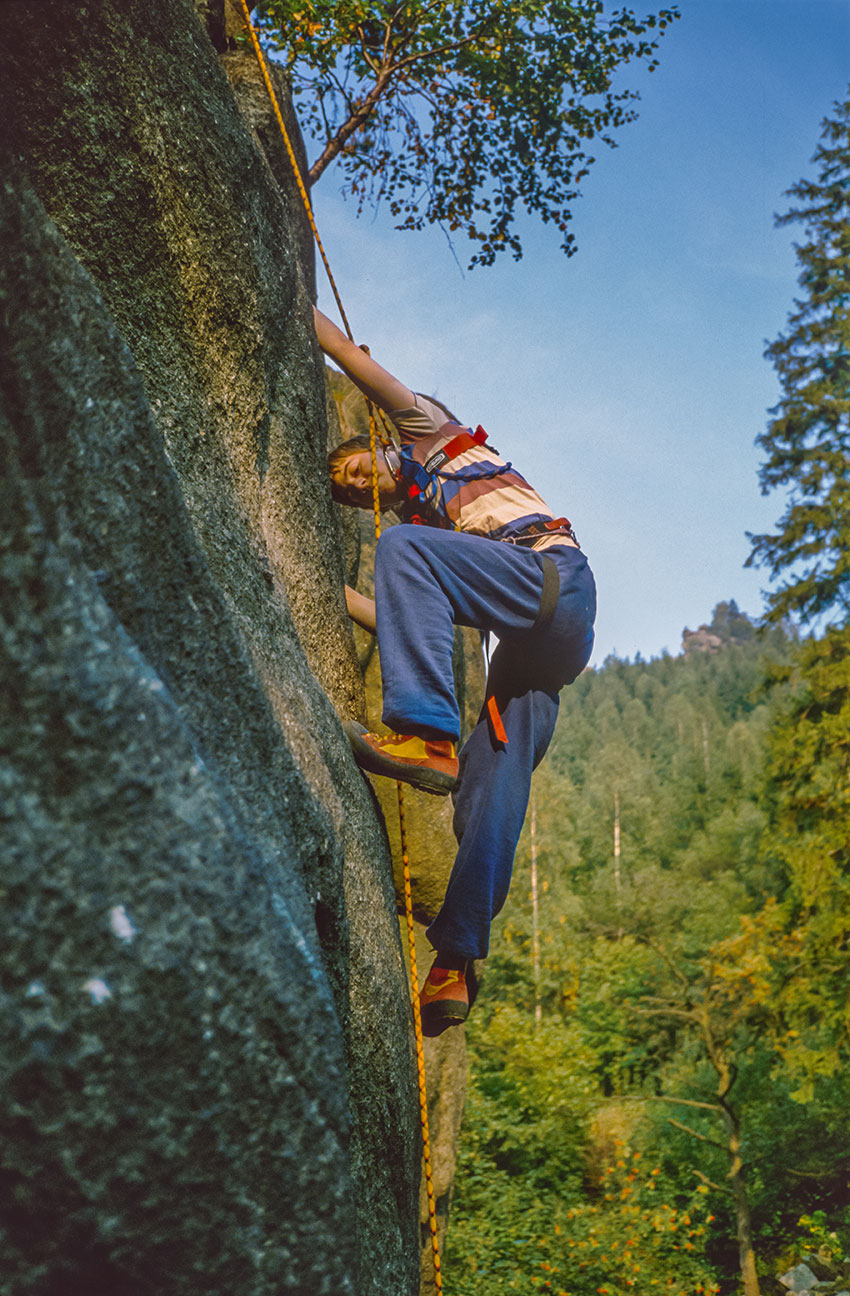

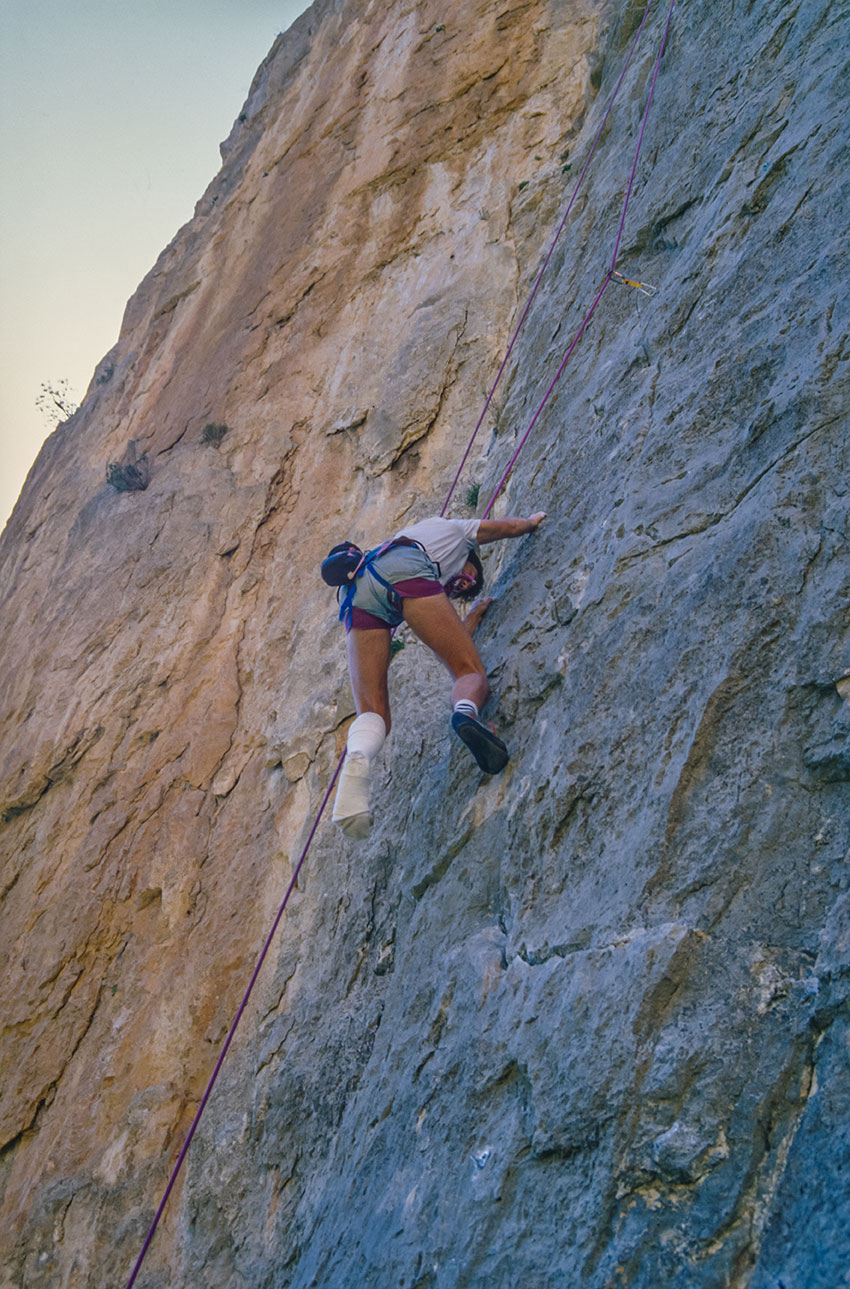

Mathias: I definitely enjoyed it. Because every time you give something, you also get something back. Even if it’s just the joy of the other person. And, yes, that’s definitely how I ended up doing community service. It was organized by the church. And then a leisure activity was planned for the elderly in the Odenwald, for three weeks. I was allowed to go along as a driver, with a minibus, to chauffeur the guests around. And of course everyone knew that I climb. And, yes, then of course I tried to combine business with pleasure. And the older ladies in particular let me go climbing somewhere in the afternoon. I then went off with a rope and jumar and ended up at the „Stiefelhütte“, which is a quarry. And, yes, there was a route that was, well, in my prey pattern, 8+/9-, the „Crepuscale“. And, I was able to climb it relatively quickly with the jumar. But of course I wanted to lead it. There was just no one around.

Jürgen: But who is belaying?

Mathias: Yes, who is belaying? And I thought, well, somehow I have to see if it could be interesting for the older folks to see what climbing is like. So we carted them all to the quarry. I know there were 20 or 30 people there. So we all went there, it’s a flat driveway, and in front of it is a beautiful green meadow with benches.

Jürgen: Ah, so they could sit then?

Mathias: Yes, they could sit.

Jürgen: With benches even?

Mathias: With benches even.

Jürgen: That’s perfect.

Mathias: Well, really perfect. First of all, I climbed a 6+ edge there. And the pastor, well, with God’s blessing, I climbed there, belayed me. Well, there are still photos of that, yes. And then I asked the pastor if he would belay me briefly on a slightly more difficult route, and so I was able to get the red point of the „Crepuscale“ route after all.

Jürgen: Perfect. Did everything go well?

Mathias: Everything went well. Yes. Well, there are also fall pictures. So, I jumped into the rope for them to show that it’s not dangerous. And, yes, I think we all had a great day.

Jürgen: I also think that’s an experience, right? Yes, great. Well, that’s really great that you combined it in that way, so to speak, in this case, that, yes, what is a bit of a duty, yes, the service, but then make it so pleasant and take the other people with you and that again. Great. I’ll give you another keyword. You mentioned hiking earlier, hut-to-hut hikes were your introduction. What comes to mind when you hear the keyword ‘ice climbing’ and think of the Stubai Valley? I think you’ve also tried that.

Mathias: Yes, ice climbing, my parents weren’t allowed to know about that.

Jürgen: Oh, okay.

Mathias: Yes. And that’s why, well, shh, no. (Laughing) Well, I had planned a hut-to-hut tour with my buddy Ingo through the Stubai Valley. And that was the very first longer undertaking outside of these weekend excursions that our parents approved. That must have been around the age of, well, 14, 15 or so. So, really quite young.

Jürgen: Did you hitchhike back too?

Mathias: I think we took the train that time. So, that was a longer planned tour then. And then the parents said, well, you are welcome to go hut-to-hut trekking. Yes, they knew that themselves, they took us there themselves. But no climbing or ice tours.

Jürgen: Well, okay. (laughter)

Mathias: First we did the „Habicht“. That’s a bit of climbing. And then, then the „Zuckerhüttel“, that’s pretty icy already. And, yes, then we actually had all the ice tools with us. So, not just the long hiking axe, but also somehow the Lowe Hummingbird ice hammer.

Jürgen: You hid that cleverly, so that it wouldn’t be noticed when packing.

Mathias: Somehow we managed to smuggle it in, exactly. And, yes, then I also have to mention that this is actually the first time that something bad could have happened, that was even before the Donautal accident, I mean. That could have ended my career. We then ended up doing something like an ice couloir. And we didn’t take a helmet with us for a hut-to-hut hike. And, yes, somehow there was a rockfall. And I didn’t even really noticed it, I had both ice axes up, my legs kind of spread out, and I just heard this “pfiu-pfiu-pfiu” like from a rockfall. And then a rock whizzed between my arms and between my legs, and nothing happened. But it could have just made a small hop. Without a helmet.

Jürgen: Jump ten centimeters further away.

Mathias: Exactly, that could have been the end already.

Jürgen: So there was the pastor and the assistant there again.

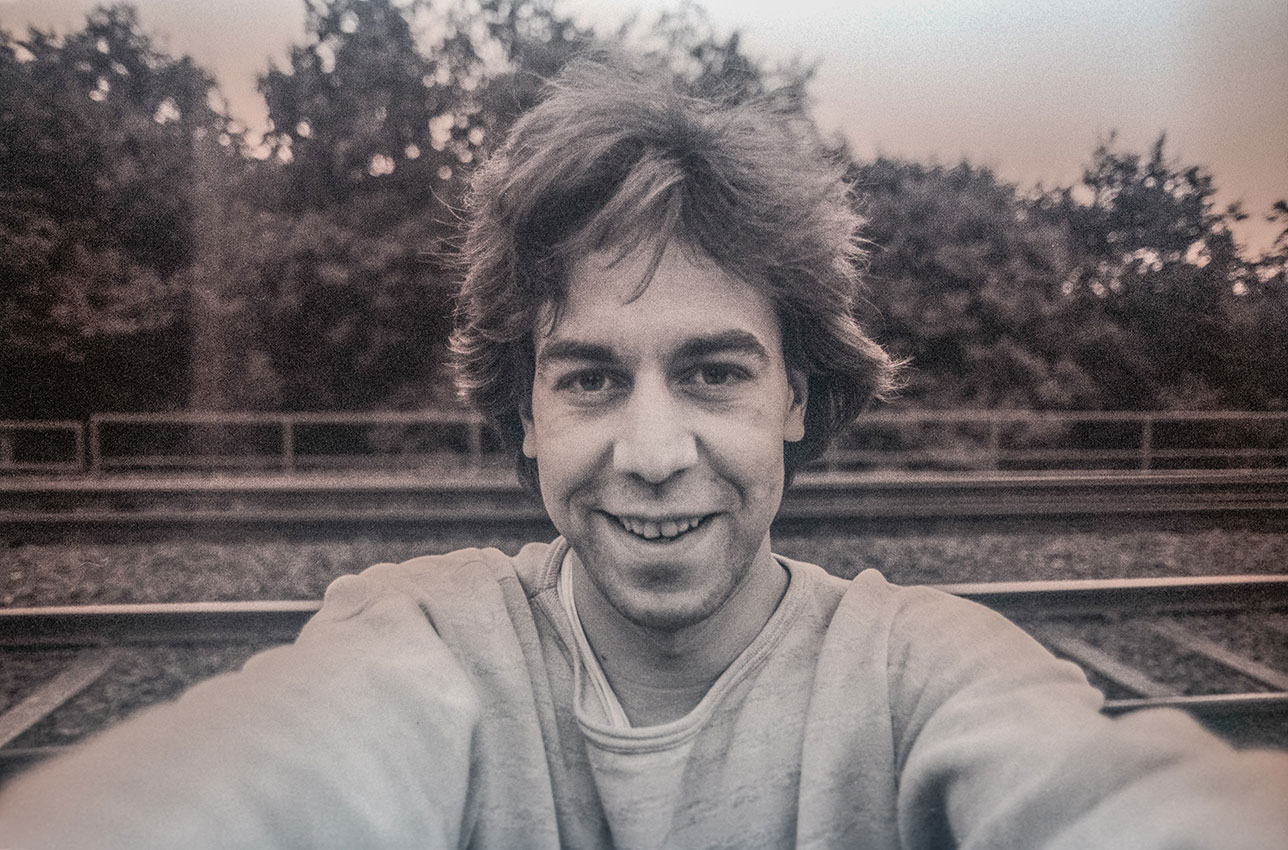

Mathias: Yes, exactly, yes. Then I came home, full of wonderful experiences. And I wanted to tell my parents a lot about it. Of course not everything. And I was met with pretty angry face. So I thought, oh, what’s going on now? What happened, I had made slide films. So, these are the ones that you project to a screen with a slide projector.

Jürgen: Yes.

Mathias: And I sent them from on the way, to have them developed already. So when I get home, I’ll probably have the pictures ready by then.

Jürgen: And your parents picked them up?

Mathias: My parents had already looked through them, at what here boy does. And so they knew exactly what I had been up to.

Jürgen: But was it because you said that your parents had given you a lot of support and knew that this was your great passion, was it a change?

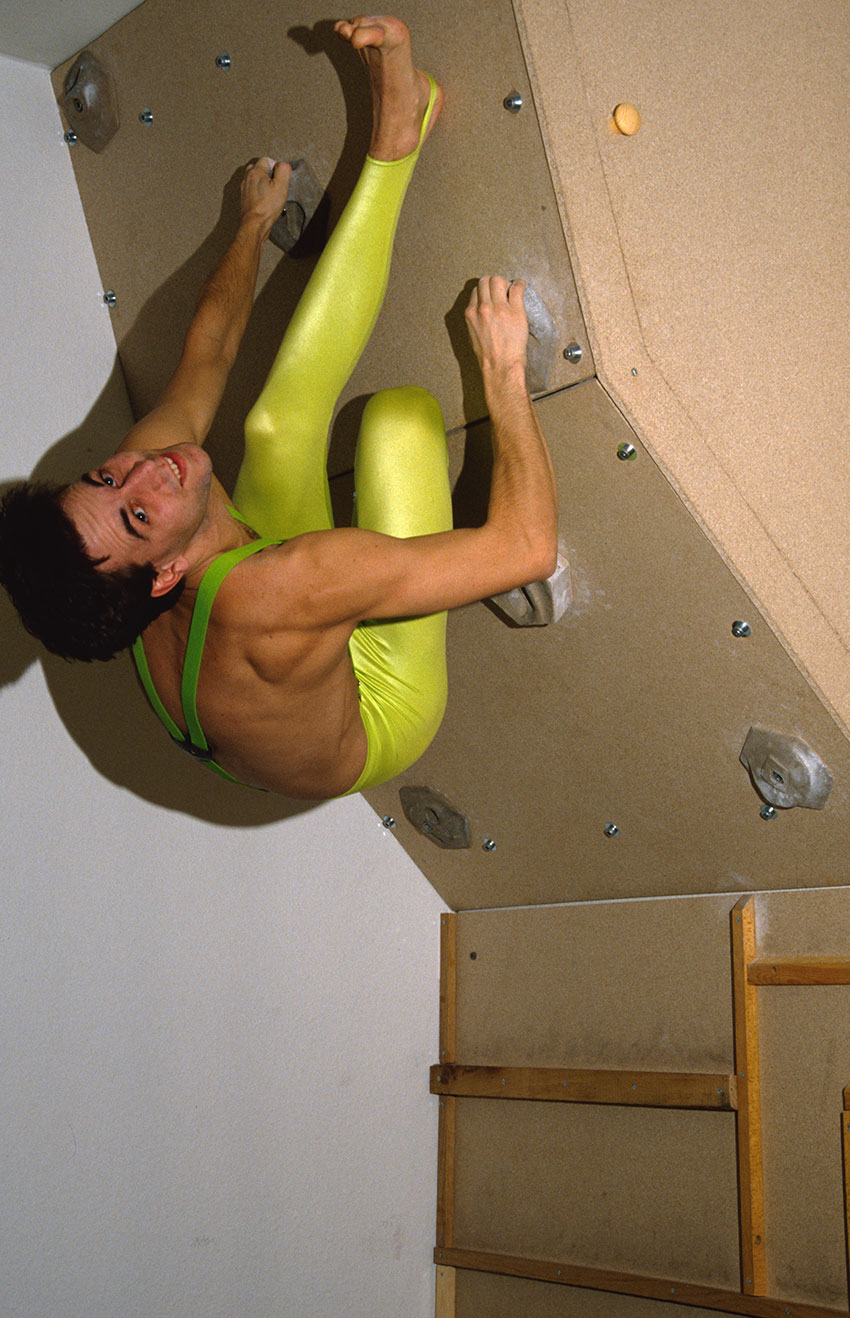

Mathias: No. Well, it wasn’t always the case that they… Well, there was a small incident in later times when my father didn’t just talk to me for two days or so, but it was more like two weeks. My parents were on vacation then. And my father liked to play with me with the train set, the model train set. And then there was a train set that could somehow be pulled up under the ceiling in my room. No train ever ran on this train set. And that was a bit frustrating for me. But the deal was, the set stays up there until I move out. My dad bought it already from me, to support me with money for my climbing equipment.

Jürgen: Okay.

Mathias: But then I got it into my head that I needed my own little training wall. Just an overhang, you know. And well, the parents were on vacation, so in no time at all the railroad plate was taken down and hung in the garage, and when they came back…

Jürgen: But you hung it there obediently.

Mathias: I hung it up there, yes. And I welded steel girders together myself. And that was also…

Jürgen: As a substructure?

Mathias: Yes, exactly. That was certainly a great technical achievement. I think the parents were proud of that too. But my father didn’t like the fact that the railway plate was dismantled. But he forgave me for that too. I have very tolerant parents.

Jürgen: But you actually built your own climbing wall, too. That’s crazy

Mathias: Yes.

Jürgen: There wasn’t a blueprint that you had that you could use, but it was simply your own idea of how to do it?

Mathias: Yes, well, at that time, I think it was just starting with the commercial climbing walls. In Hamburg, I think it took another ten years before anything was established. And it even went that far, that at the age of 24, my parents asked if I might not want to move out soon. And I said, why? We get along well. I didn’t see any point of moving out. I had just expanded the climbing wall even further. And yes, I then started an apprenticeship as a photographer. And then my parents said, yes, we would support you to such an extent that you could continue to drive your own car, which you had bought during your civilian service, so that you could get to the rocks. And I persuaded the uncle, in whose apartment I moved in, to give me another half room where the climbing wall could also be moved. That was a very important factor at the time. Yes. (Laughter)

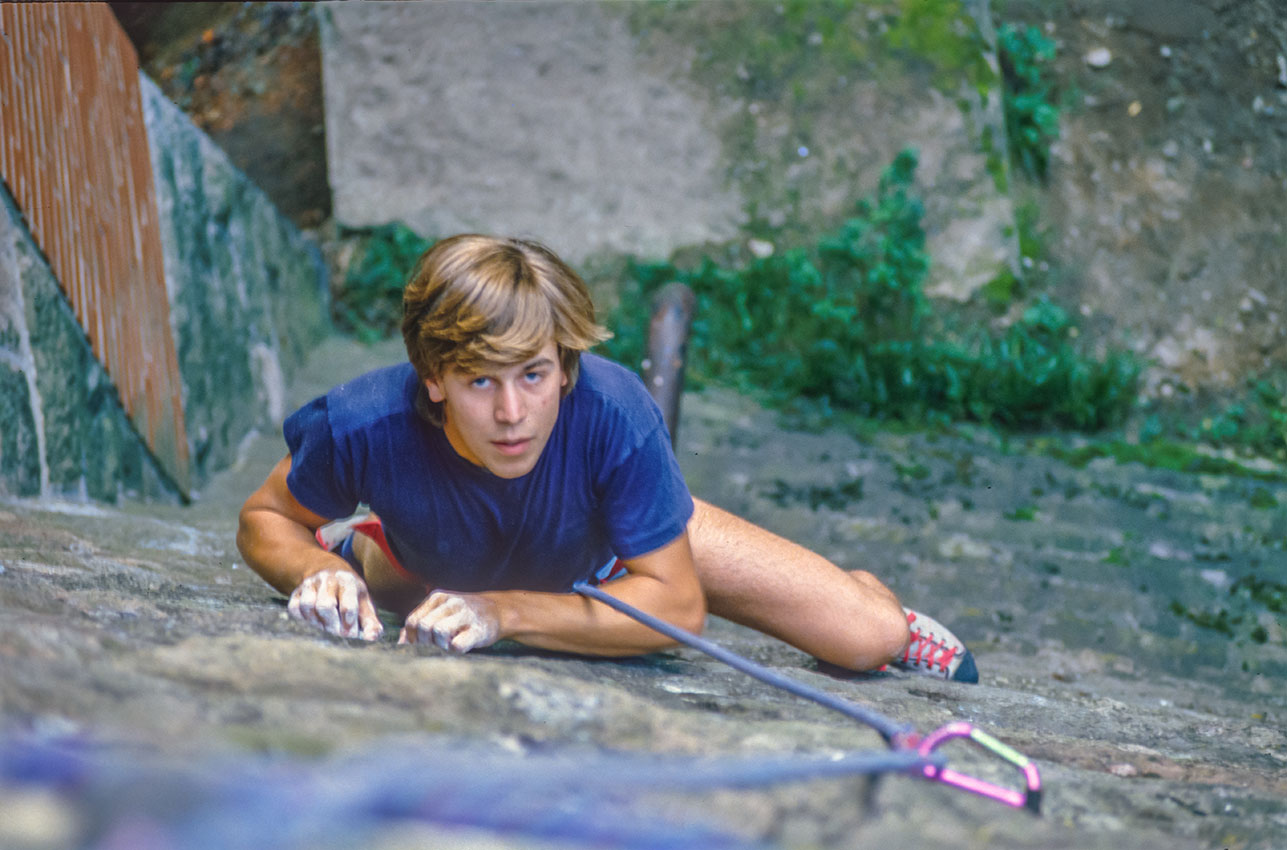

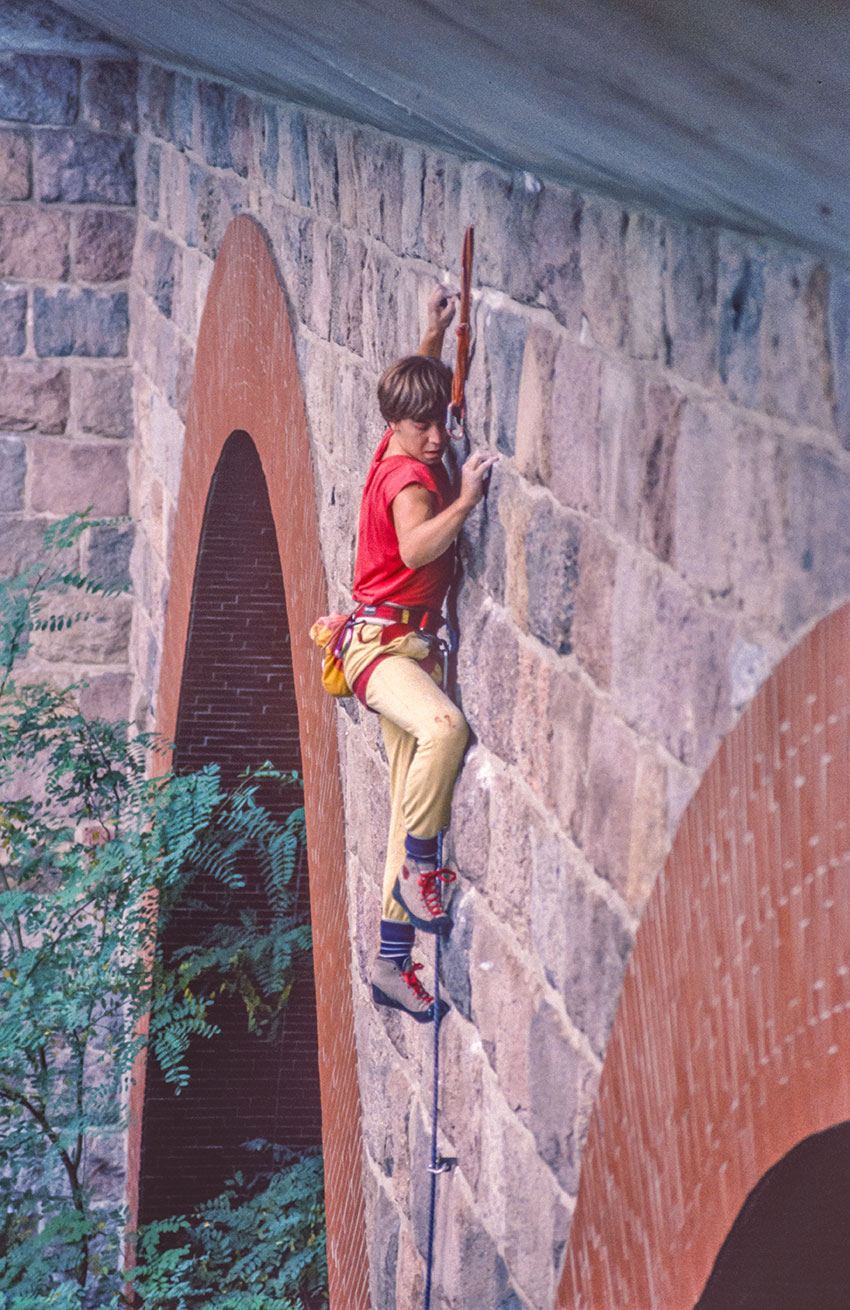

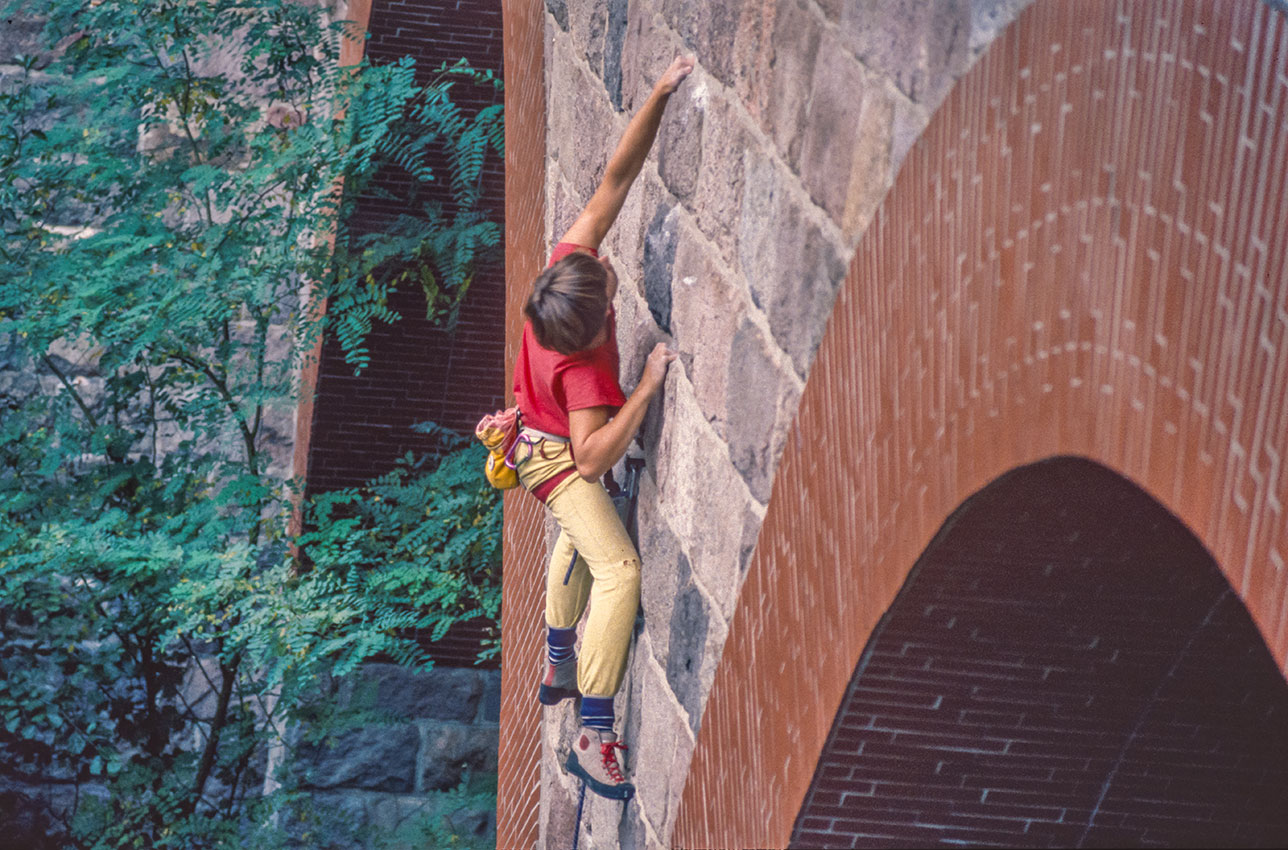

Jürgen: Very nice. So that was ice climbing. Yes. And you also, because you just mentioned training and the climbing wall, you also trained on bridges?

Mathias: Yes. Well, that’s where it started. Mhm. – Sorry, you wanted to…

Jürgen: No, that was it. – Okay. (Laughter)

Mathias: That’s where it started, on bridges. So, even before my first own climbing wall… Well, Hamburg was always at least two and a half hours of driving away from the first rocks. And hitchhiking didn’t always work out so well that you could get through it so quickly. And yes, and then… The passion was just so intense, I could have gone climbing every day. And yes, then we just looked for railroad bridges, well, the bridge piers that were build out of natural rocks. And, of course not necessarily with the blessing of the railroad police. We actually just smashed pitons into the joints and then celebrated the whole thing as a first ascent and wrote the route name on to the base. And what happened later on was that when we got caught, we were charged for trespassing on the railway embankment. And that cost five Deutschmarks each. We didn’t like that. Five Deutschmarks was still a lot of money for us. So we said that there was only one of us who went up there to fix the top rope.

Jürgen: You negotiated right away.

Mathias: We negotiated right away. They let us get away with it. One of us paid five Deutschmarks.

Jürgen: So 2.50 for each of you

Mathias: Yes, that was kind of cute, yes.

Jürgen: Did they come more often after that and sort of monitor your climbing? Or was that a one-time thing?

Mathias: Well, we only got caught that one time, but, yeah.

Jürgen: Okay, you also had, or I said that in the intro, there was a, I think it was a project from school, an „experimental human picture“. And a bridge also played a role.

Mathias: Exactly, that’s a very funny story. At that time I was already in the photographer apprenticeship. And we got the task from the vocational school, from the art teacher, to photograph an experimental human picture.

Jürgen: Whatever I can imagine under it.

Mathias: Yes, that was the creative factor. And I photographed my girlfriend from Paris at the time. There was a fair in town, a carnival. There was a hall of mirrors, and I photographed her in it. So in black and white, they were artistically interesting shots. Then I did some nude shots of her, on the roof of the building, above the rooftops of Hamburg. I thought it was relatively experimental. The day before I was supposed to hand it in, my girlfriend had left for Paris. And as I realized afterwards, she didn’t really agree with the shots and stole the negatives from me.

Jürgen: Oh, ok.

Mathias: That means that was then…

Jürgen: You had nothing to hand in.

Mathias: I had nothing to hand in, it was extremely urgent. And Carsten Wottke, my climbing buddy at the time, was always good for extremely creative ideas, where you had to cut a few corners because otherwise the idea might have been fatal. (Laughter)

Jürgen: So, again, a backup with install, yes?

Mathias: Exactly, yes. And then he says, „just jump off the balcony and photograph yourself doing it“. Balcony, second floor.

Jürgen: I’ll deliver it for you.

Mathias: Exactly. And then I told him, well, actually a good idea. We just have to modify it a bit. Do you have time this afternoon? We’ll meet at the bridge. I stood on the railing, tied on a rope, like the Kine-swing you mentioned earlier, just a bit modified.

Jürgen: Ah, yes.

Mathias: And like a bungee cord, so someone is standing at the bottom, and then you get pulled up, and the impact force is absorbed relatively softly. I held a camera in front of my face and then took one or two pictures in flight with my hair standing on end.

Jürgen: You took a selfie with a camera like that?

Mathias: Yes, exactly.

Jürgen: Okay.

Mathias: And the art teacher liked blurry pictures, and that’s exactly what he got. And so I got an A for a picture that I didn’t really like that much. I had planned something different.

Jürgen: But tell me, the thing was valuable, right, your camera? You can’t drop that?

Mathias: No, you have to hold on to it.

Jürgen: Do you have it secured to a strap again?

Mathias: Maybe with a sling or something, but I don’t remember. It was clear that I wouldn’t let go of it. (laughs)

Jürgen: Crazy, crazy. Okay, so that was in Jesteburg, with that bridge. If someone ever comes to Jesteburg and sees that bridge, think off that there where some experimental human pictures been taken. Very nice.

Mathias: Yes, there were maybe some funny situations. In Hamburg, a lot of media stuff happened. We were shooting at the highway bridge in Stillhorn for a TV show. And then the police came. And the cameraman, with great presence of mind, held his camera up and filmed the police officers. And that was so typically German. “What are you doing here? Who is in charge? Do you have a permit?” (laughter) It’s all on video. And that was pretty funny.

Jürgen: I’m sure. Okay, so then you decided to go out into the big, wide world and not just stick to the bridges. And I’ll pick on one because there was, and still is, the Alpin magazine. Back then, there was also Andreas Kubin. And something was presented there, a legendary route for me: “Lunabong in the Verdon Gorge”.

Mathias: Yes.

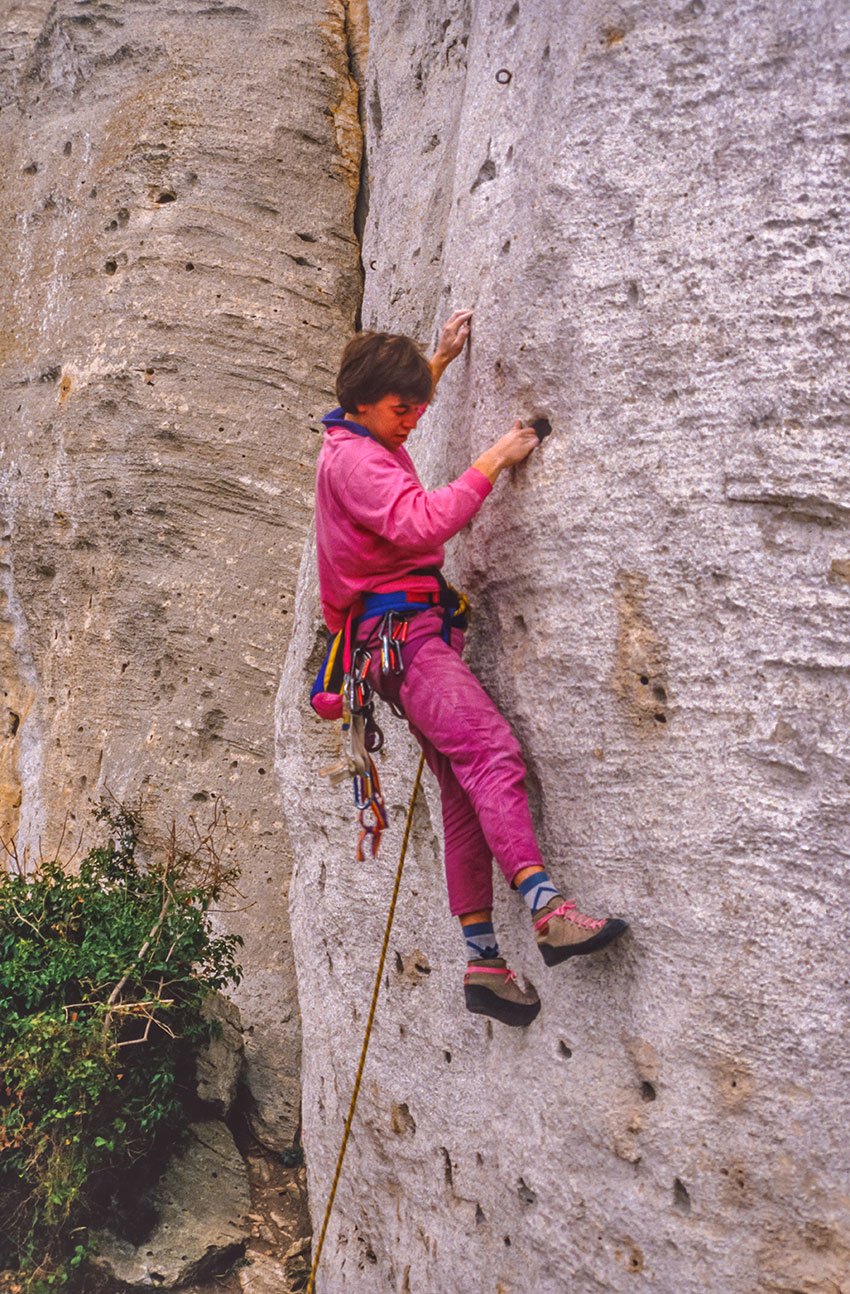

Jürgen: What about your ascent? And why did you go there on a tip from Alpin magazine and Andreas?

Mathias: Yes, that was… slab climbing was actually always what I was best at. Not so powerful but technically, I always had a good technique. That’s where I was always able to push my limit a little further. And yes, in magazine „Alpin“ there was a beautiful picture of this route „Lunabong“ in it. Slab climbing photographed from above. As we found out afterwards, that’s the only two meters of slab climbing. The rest is hand crack climbing, most of it is, I think…

Jürgen: Then something else is required.

Mathias: Right, exactly. And we definitely couldn’t do that back then.

Jürgen: Now you also have to say that the Verdon Gorge is something special when you arrive from above and rappel down.

Mathias: Exactly.

Jürgen: That means you have to somehow get back up.

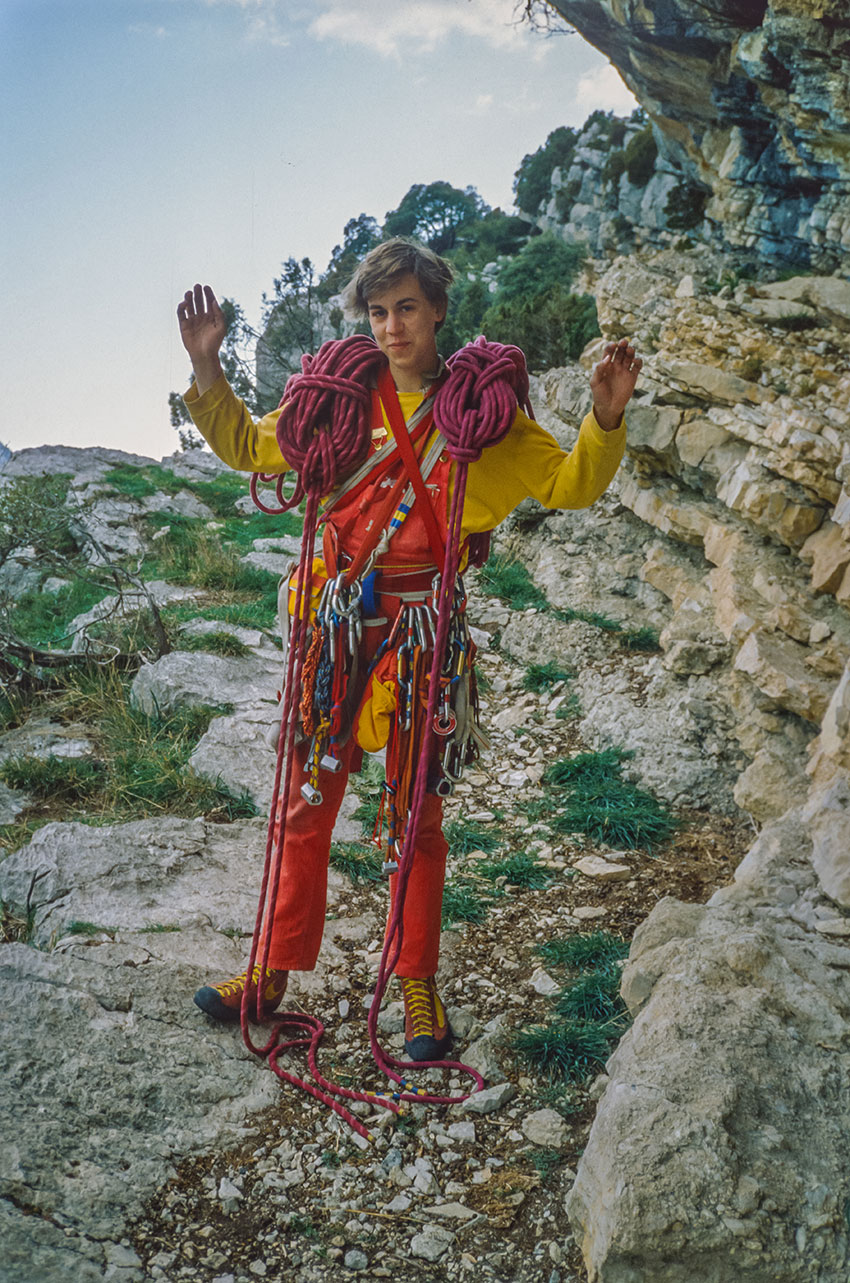

Mathias: Right. And that was exactly what became a trap for us. Well, we had to hitchhike down again. So, it took four days to get to the Verdon Gorge. One day through Germany was always easy. From highway rest areas to highway rest areas. In France it was really hardcore. There it was really difficult to hitchhike. We slept under highway bridges, in some ditches next to the road. It was quite an adventure to get there. But also experiences that stick with you. And…

Jürgen: But the only thing you had was practically really the report by Andreas Kubin. Because you said, we really have to go there.

Mathias: Right, exactly. And it said in there, great introductory climb. I lately had a nice chit-chat with Andreas Kubin on the phone, when he contacted me because of some climbing pictures I took in his home crag Pfalz that impressed him. I rubbed his nose in it, that we pretty much got stuck in his “introductory climb”. Because we rappelled down and saw that it wasn’t slab climbing at all. But we still rappelled all the way to the ledge where the route starts. We somehow fought our way up for two pitches, realized that this was not going to work at all, that it was way above our limits. We said, okay, we’ll rappel back down and then take a leisurely walk back through the canyon. When we got back to the ledge, there were even red markings. We thought, great, there’s a hiking trail, we’ll walk back nicely afterwards. We even did some bouldering on the ledge. Then we followed these red markings and after 20 meters we realized that it didn’t go any further, next stop. I rappelled down another 20 meters or so. It was overhanging, crumbly terrain, there was no way to get down. That means I had to climb up the 20 meters again, with prusik loops, I was completely exhausted. Then it was already getting dark and we said, well, let’s go. Let’s try to get up there again at dusk. After two pitches, we were back at the same place as before and had to bivouack on the small ledge. If you have been in Verdon in March, it is really freezing cold. Night frost and, yes, Carsten had shorts on as always.

Jürgen: Can vultures circle overhead, too?

Mathias: I don’t think anything circles at night.

Jürgen: No, certainly not at night.

Mathias: But you could have heard us quite well because of the clattering. Carsten with a long T-shirt and shorts and me with a short-sleeved T-shirt and long pants. And luckily we had a helmet back then and a rescue blanket in the helmet. And that made the night a bit more bearable for us. We really huddled together without really having anything to eat or drink with us. In the morning at sunrise, we then continued through the route and at the top of the last stand, the first rope teams came, who abseiled, and stepped on our fingers when we tried to get on to the belay, yes, that’s one big Tree root. And they said, why are you so stupid and climb so early? (laughs) Yes. Anyone who knows me knows that I am not an early bird.

Jürgen: But you didn’t say anything, I think you were just glad to get out again.

Mathias: Yes, we were very happy to be get out of the climb, yes…

Jürgen: Crazy. Well, I mean, I also found Verdon incredibly impressive, but of course it’s even more intense when you’re actually have to bivouac in the middle of the gorge. That’s pretty impressive. Respect. (laughs)

Mathias: These are the experiences that you remember in old age and can tell about. Of course, in retrospect, I wouldn’t want to have missed it.

Jürgen: I also love it when you say, if I see something, the article, we have to go there. I know that exactly the same from myself. Something like looking at Topo carefully doesn’t matter. I was also in the Verdon Gorge with a friend. It was my first time there, he had been there three times. I opened the car door, threw the rope down at the abseil point and went down. And he… “Which tour did you come in?” “It doesn’t matter, the main thing is climbing.” (Laughter) Yes. (Clears throat) Okay, that was Verdon. And that was a bit bigger than the bridge, so to speak. But you didn’t let yourself be stopped. You really got into the mountains and climbed three north faces there. And… let’s start with one… The Eiger, that’s an impressive wall, an impressive north face. How did you get the idea to climb this north face? What was your motivation?

Mathias: Yes, well… I already mentioned it at the beginning that I got into climbing through the Alpine Club. And as a teenager, I spent practically every free minute in the Alpine Club library. I read my way through the entire library. After school, I still went to the Alpine Club when the library was open. And yes, I read about… Hermann Buhl, “Eight-thousanders: A Climber’s World”, Heinrich Harrer, “The White Spider”, Eiger North Face. Of course I read all these heroic stories. And… Yes, that naturally awakens desires, let me put it that way. But at that age, I would never have dreamed that I would somehow make it there. But of course these images were somehow always there in my mind. And… I already said earlier that images have always influenced me a lot through photography as well. And… then Reinhard Karl is one example. Well, the two photo books that particularly impressed me the most were the one about Yosemite. And then his photo book… I can’t remember it right now…

Jürgen: “Hardly Time to Breathe”.

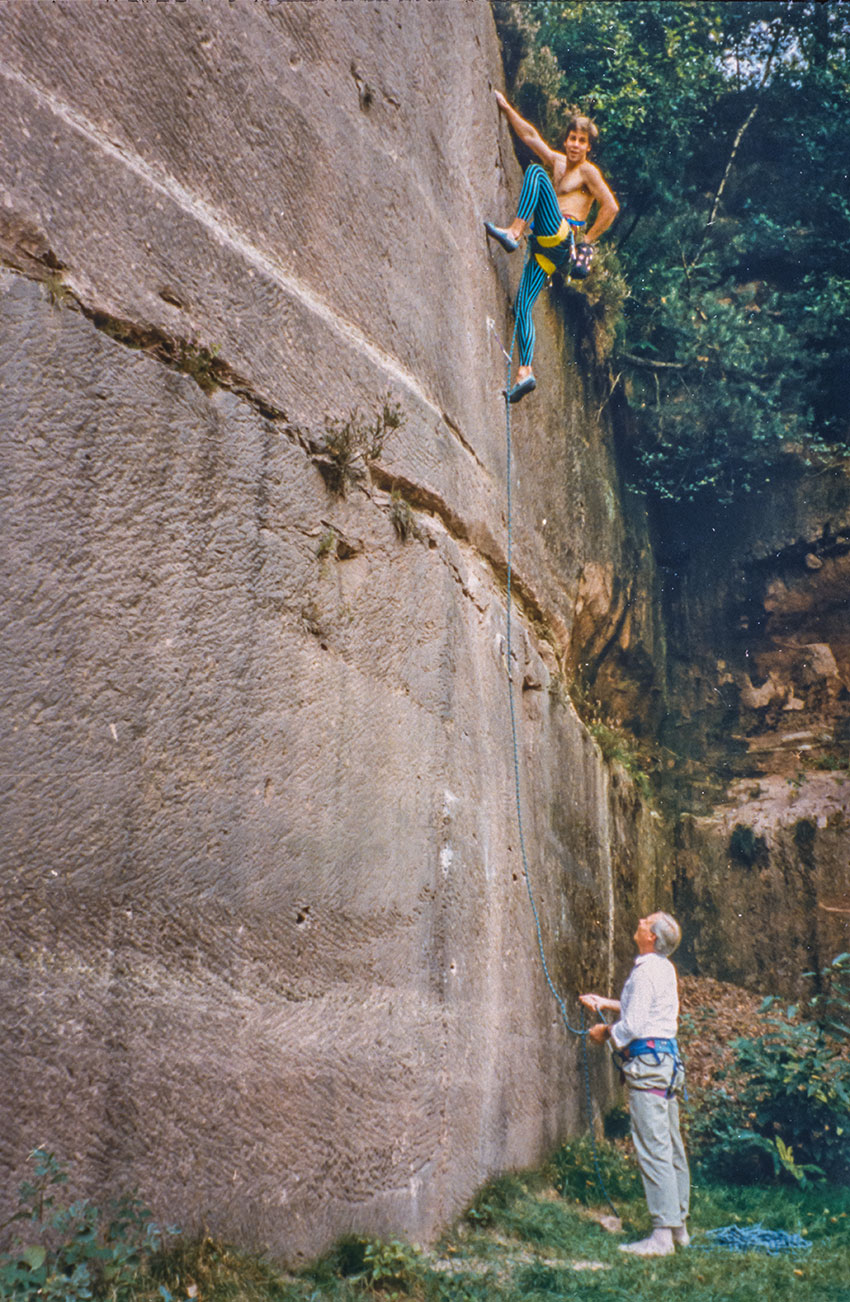

Mathias: Exactly, “Hardly Time to Breathe”. Exactly, thank you very much. And so these pictures, which simply went beyond that, beyond the documentary aspect of mountain photography, and brought something artistic to it. But of course there are also these stories. Well, what Reinhard Karl had also experienced. Well, climbing in the low mountain range. That’s where you build up experience for the bigger alpine walls first. And then there are just these really big walls. And then it was actually… Yes, as always, it was a bit of a coincidence. I had planned an alpine vacation with Carsten Wottke again. And we had really considered every area we wanted to go to, so starting with the „Wilder Kaiser“, we wrote us a list with a “top-of-the-list route”. If it goes well, we’ll do this one at the end.

Jürgen: What was the “top of the list” in the Wilder Kaiser back then?

Mathias: “Top of the List” in the Wilder Kaiser at the time was the Pumprisse.

Jürgen: Pumprisse, yes. Helmut Kiene, all right.

Mathias: And well, at a young age you’re sometimes a bit megalomaniac. And then at some point it occurred to us that we could just do the big stuff right from the start. And that was the case with the „Pumprisse“. We were also very lucky there. Well, we actually went through the… well, we were just in this so-called „Hundebahnhof“ (Offwith crack). For those who don’t know the climb, it’s the first seven in the Alps. It’s a crack climb. Mostly hand and fist jams. And a crack in the seventh grade at the time, that was just… well, really, that was an announcement. And then a thunderstorm caught us above the „Hundebahnhof“.

Jürgen: Now it has to be said that Hundebahnhof comes from the Saxon climbing area. Right, exactly. You can get a bit of a feel for it there.

Mathias: Right, yes, but in this case, we only had one friend size four with us, which then had to be pushed further and further up. Otherwise, only these big hexentrics, which didn’t really fit for that crack size. And that was actually quite scary with the protection. And then to really experience a sudden change in the weather. So, with thunder, rain and hail. Carsten again long-sleeved shirt and shorts. So, we skipped the last two pitches at the top, which are also 7-, we chickened out because everything was just wet, climbed out to the left through some kind of chimney. But okay, that was the first step in laying the foundation for tackling the bigger things right away. And then we went to the Bernina area next. And at the top of the list was the Piz Rosseg northeast face, some ice climbing, 50, 60 degrees steep. We did that right away, and it worked out well. And then, I don’t know if it was luck or bad luck, nothing really worked out in Chamonix because the weather got bad. So we drove over to Lake Garda. And then Carsten got homesick and went back to Hamburg to be with his girlfriend. And I met another buddy there, Klaus Dethfurth, who unfortunately has since died in an climbing accident. But he was also totally hooked on alpine climbing. And he also said, I’m just waiting for good weather here, then I want to go back to Chamonix. And then we went together, went back to Chamonix, and actually did a preparation climb. In this case, it was a traverse of Mont Blanc. If you come from Lake Garda, which is almost at sea level, then it’s quite tuff, we really got a good workout.

Jürgen: So in terms of acclimatization too?

Mathias: So up to the Aiguille Du Midi at 3900m by cable car, then down into the Vallée Blanche at 3700m, then up to Mont Blanc du Tacule at 4200m, then down to the col at 4000m, up to Mont Maudit at 4400m, down to the col at 4200m and finally up to the peak of Mont Blanc at 4800m. We were pretty exhausted when we arrived at the bivouac box and people told us we couldn’t bivouac there anymore because the box was full.

Jürgen: The box was full, yes.

Mathias: Then we said we just wanted to lie down for half an hour, then we would continue our descent. We woke up the next morning, we were so knackered. We couldn’t go on.

Jürgen: That’s a good trick, yes. I just want half an hour, then I’m off.

Mathias: But okay, we had acclimatized. Then we said, come on, let’s try something bigger. We were, let’s see, I think we went to the Dru, so anyway, we went up towards Petit Jorasses, we wanted to do the Petit Jorasses west face. The weather was great, there was another Austrian rope team there that had the same goal, so we got to talking nicely. And I thought, well, if that goes well, then we could also do the Walker. Or something like that, and then I thought, well, we might as well do it right away. So we didn’t do the Petit Jorasses and did the Walker straight away. And we got through it quite well. And yes, then it’s a bit like that, you have a north face, so there are just three big north faces, the Eiger north face, the Matterhorn north face and the Walker pillar. And then somehow the call is there, then the other two also call. And then I met Rollo Steffens at the Pierre d’Orthaz campground in Chamonix. And he had already done the Walker and was keen on the Eiger too. And then a few days later we went to the Eiger together, and first of all, I don’t want to say we got hit on the head, but we have a wall that is somehow three kilometers wide. And if you’ve never seen the wall before, you shouldn’t presume to want to get into it in the middle of the night at three or something. You just can’t find the start of the climb.

Jürgen: I was just going to say, in terms of orientation, yes. Preparation is everything.

Mathias: Preparation is everything. And then at some point in the morning, when the sun came up, we turned back, realized that we were almost a kilometer away from the start of the climb. But then came back in fall, much better prepared. And if anyone is interested, we did the Heckmaier route. It’s a climb that you definitely can’t do in summer anymore because there’s so much rockfall due to the melting permafrost. We did it at the end of September…

Jürgen: That’s when you really notice that climate change is having an effect.

Mathias: Yes, totally. Back then, it was really two-thirds an ice climb. Even then, the waterfall chimney was an ice climb.

Jürgen: So it was a completely different climb. Mixed climbing, with a lot of ice in it.

Mathias: Yes. And… Yes, there is another funny anecdote. I might have to go back briefly to the descent from Walker pillar. We will be discussing this topic again later at IG-Klettern. So that people will remember this podcast as the fecal podcast.

Jürgen: Oh dear, I’m curious. Then let’s hear it, Mathias.

Mathias: So on the descent from the Walker, the last few hundred meters to the hut, I thought I would take an excellent shortcut and wouldn’t even have to run down the whole slope and up again. I thought I’d cross over to the hut. I realized that this wasn’t such a good decision when I was practically up to my ankles in shit because…

Jürgen: Damn it!

Mathias: Because the outhouse was above the hut. With plastic mountaineering boots, it’s no fun.

Jürgen: Oh, that’s not nice.

Mathias: I sat there all evening scraping the shit out of my boots.

Jürgen: Oh, okay. Thank God for chemical toilets, where you can’t just drop it down.

Mathias: Yes, exactly. But it was still like that back then. And on the Eiger it was quite exciting. We… well, maybe lets start from the beginning, coming from Hamburg. And there, too, it was the same old story with the acclimatization. But we didn’t want to make the same mistake as in the summer, going up the wall in the dark. We’re decided to start in the afternoon, find the right starting point and then just bivouac after…

Jürgen: And then just do two or three pitches.

Mathias: Exactly, so we drove straight through the night from Hamburg and then started climbing in the afternoon the next day. We then bivouacked for the first time below the first pillar and wanted to leave at the crack of dawn. Unfortunately, we didn’t have an alarm clock with us. When we woke up, we were already quite overtired from the driving, of course, the cable cars were already running on the Scheidegg and the sun was shining.

Jürgen: Well, you guys… it’s not every day that a bivouac feels so cozy.

Mathias: Exactly, so we had sleeping bags with us, so we were really well prepared, each of us had a camping mat that we had cut to size, which folded three times and served as a back wall in the back of the backpack. And so we really stretched out on it and slept well. And we definitely wanted to reach the „Death Bivouac“ that day, because we knew it was a good bivouac spot. After the first ice field and the second ice field, where you traverse through the whole wall for ages. And it was really pitch dark when we arrived below this part of the wall, called „the iron“. And we said, okay, we won’t reach the „Death Bivouac“ anymore, lets bivouac in the edge crevasse between rock and ice. We shoveled out enough space to have a nice surface to lay down again. So that was a great bivouac spot. But yes, I always have to go to the toilet first thing in the morning, number two…

Jürgen: Nature calls.

Mathias: Nature calls, yes. Then I led the pitch up to the „Death Bivouac“. And well, it was fall, we were alone on the wall. And yes, dungarees off. It was still a chest strap-hip belt combination back then. Everything had to come off so that the pants could come off. And at that moment, so I’m standing there, the ledge is really wide enough up there, yes, I’m standing there with my pants down and I notice that the topo is falling out of my dungarees at the front. And I started to row like that.

Jürgen: You have to row because the topo is important.

Mathias: Yes, but thank God I left the topo behind. Otherwise I would have flown afterwards, unroped. And luckily Rollo also had the backup topo in his front bib. And then we shared the one topo.

Jürgen: Exactly, that would have been my question. Because seriously, you always need a backup. Everyone should just have the topo with them, know all the necessary information, okay, okay. But then you got through well?

Mathias: We thought, “We’ll do it better the next day.” We won’t get into the dark again. We were then at the „traverse of the gods“, there was a great bivouac place. And we said, well, do we still want to dare to get to the summit? Or do we make a bivouac here? And we sat and sat and waited and waited. Until the sun finally went down. But it was really beautiful. It was the time when the Walkmans came out. That means, tape players…

Jürgen: And you could also enjoy the landscape with music.

Mathias: Everyone had their own walkman with them. I listened to “Dire Straits – Brothers in Arms”. Rollo somehow listened to “Nena”. And it was beautiful, the bivouac. And well, the next day we somehow made it to the summit. And then back down again. But in the end we spent three and a half days on the wall. But we knew that the weather conditions were very stable. It was incredibly cold, but… it was a joy. I should maybe also mention that… we were both in love with the same woman when we went to Eiger, Frauke Müller. And Rollo thought I was with Frauke already. And I thought Rollo was with Frauke. We both went to the Eiger totally love sick. Thinking, never mind if the mountain would kill us. And then, during the climb, we told each other our stories. After then, after the Eiger, Rollo had a date with Frauke. That is, we drove back to the Ith, all the way back to northern Germany. He had his date. I could tell that things weren’t going too well for them. They’re more like problem discussions.

Jürgen: You seized your chance.

Mathias: I sensed my chance. After the weekend, we went straight back down to Switzerland. And we added the Matterhorn north face to the list. And after the Matterhorn north face, I had a date with Frauke. (laughter)

Jürgen: Okay, but you were still a safe team.

Mathias: We were still a safe rope team, exactly. (Laughter) Yes, so we also had to bivouac on the Matterhorn. We completely misjudged the starter ice field. The description says that after the ice field, we should go into a couloir. Yes. And somehow we mistook the Hörnli ridge for the couloir.

Jürgen: Oh, okay.

Mathias: Yes. We almost reached the Hörnli ridge and then traversed the entire wall from the Hörnli ridge back. Unfortunately, we had to bivouac halfway up the wall, on a step that we had been picked into the ice. That was the most uncomfortable bivouacs I’ve ever had in my life.

Jürgen: Okay.

Mathias: Because we kept slipping off this step at night and getting caught by the rope. I also somehow terribly bruised my finger while hammering in the pitons, setting up that bivouac. Well, I still have the scar. And, yes, the next bivouac was at the summit. That was really great. Especially the sunrise in the morning. Although, it was freezing cold, I froze my feet during the night. Well, it was below zero, freezing despite the sleeping bag. I crawled into a rock crack like an animal. So, freezing wind up there too. But it was really this… experience, in the morning, looking over the whole Alps. There was a view as far as Mont Blanc. I don’t know if we saw the Eiger too. But it was the feeling of standing not just on one summit, but on three summits at once. On all three north faces. And that… yes, I was 18, 19 years old. Of course I was very proud after these walls. And, yes, I was… also the first Hamburger to somehow achieve that. And, yes, there is a little anecdote about that. Because… that was also picked up by the media. The “Hamburger Abendblatt”, which still exists, a Hamburg daily newspaper. At the time, it was the most important daily newspaper in Hamburg. They came to my parents’ house, took photos of me. They also asked me to show them pictures of the north faces. And then they did an interview. And, yes, then I was asked if Reinhold Messner was a role model for me. And I said that you can’t really compare us. Reinhold Messner does more of expedition and mountaineering, I am more a rock climber. Of course I knew that Reinhold Messner also did some really hard rock climbs back then,

Jürgen: including in the Alps.

Mathias: But for someone who doesn’t understand climbing and mountaineering, I just tried to give an example. I said that it’s like surfing and deep-sea sailing. You can’t compare them. And if you look at the pure level of difficulty, I was already climbing solid eights in my home cracks back then, I said then, I climb harder than Reinhold Messner. Headline, “Mathias Weck – I’m better than Reinhold Messner”.

Jürgen: Ha!

Mathias: That was so…

Jürgen: It wasn’t intentional.

Mathias: Embarrassing, yes. So, I actually got an anonymous threatening letter, too.

Jürgen: No!

Mathias: Yes, if it is on the internet these days, it’s already hard… Hate posts are unpleasant, but you can at least react to them. I couldn’t even answer, because it was anonymous. And…

Jürgen: What was the threat?

Mathias: No, not a really a threat, but it was supposed to make me feel ashamed. And, well, it was… well, very, very unpleasant. It really got stuck on my mind, that letter.

Jürgen: And the difficulty for you? You couldn’t just counter it with some sort of argument? Or could you put a counter statement in the newspaper?

Mathias: No, difficult. Everything else was well written. And it’s often the case that it’s not the writer himself who comes up with the headline, but some editor, and it has to be sensational.

Jürgen: And then comes the hook line, which is absolutely necessary.

Mathias: This in turn led to my school principal reading the article in the “Abendblatt” because it had been widely distributed. And, yes, then I was summoned to the principal’s office and he said, wow, Mathias, we are so proud of you. A student here achieving something like that. But tell me, when did you do these north faces?

Jürgen: Hm, yes… (laughs) Thank God it wasn’t specifically mentioned in the article.

Mathias: Yes, well, I think the dates were in it.

Jürgen: Oh, okay.

Mathias: It turned out that it was during the school holidays. And before the school holidays there was a project week. And you had to sign up for a group, I don’t know, sports or whatever. And I just remembered that if I didn’t sign up for anything, no one would probably notice that I was missing. No one would have noticed.

Jürgen: No one would have noticed.

Mathias: If it hadn’t been for that article in the newspaper. (laughs) Ah, yes, so you did your own project week. Well, we’re still proud of you.

Jürgen: He took it with humor.

Mathias: He took it with humor.

Jürgen: Yes, of course, if you look at it from the… Well, I’m educating myself. So you’ve done that, too, just in different forms. (Laughter) Yes, amazing, amazing. Yes, thank you very much for the insight into alpine climbing. And then you started not only doing the alpine, but you also said to yourself, man, I actually want to go to the USA sometime, but I don’t have any money.

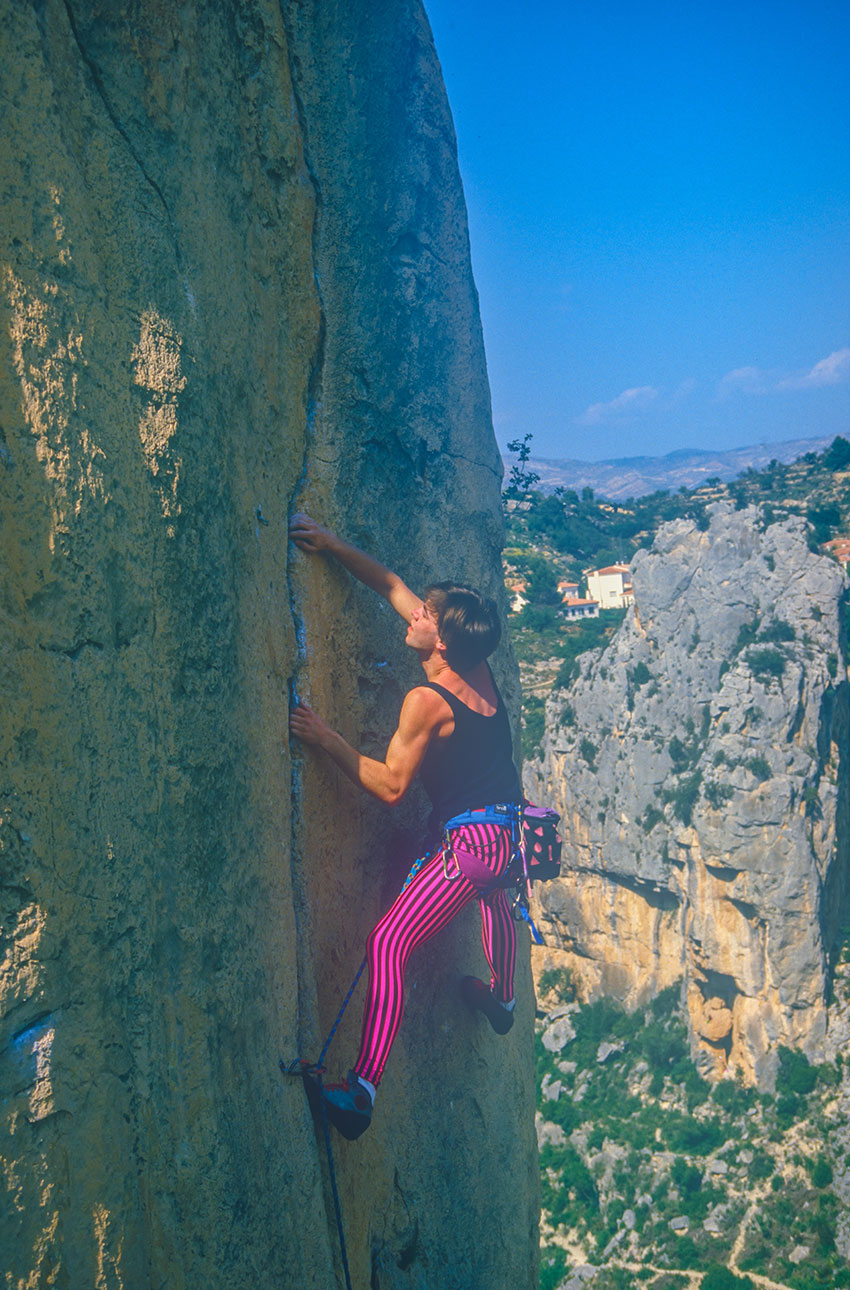

Mathias: Exactly. With rock climbing, I also startet photography, documenting my climbing. In the beginning, just with a small viewfinder camera, I simply documented what I was doing. But then, as I said before, there was also the inspiration from Reinhard Karl. So, maybe to go a little bit beyond the normal, typical mountain picture. I gradually developed a wide range of photographic techniques. I set up my own darkroom. Then… well, I kept myself busy with black and white photography. Then with slide projections. And then I started doing slide show presentations. That was after the three north faces. That was, of course, a great topic. The first Hamburger to ever achieve those things. I had a few interesting stories to tell. And I also had some nice photos, which I combined in a certain way. That was when the fade-over technique came out.

Jürgen: I think it’s called a multivision show.

Mathias: What I always liked about it was fading from one picture to another. Not just because it’s a more pleasant way to change pictures, but because the two pictures interpenetrate at that moment and form a third picture, so to speak. I started to play around with it a lot. I also did animation effects. For example, a climber moving up a wall. Then somehow a foggy landscape that then turns into the next landscape. And then I started to add music to it. And I think this first slide show I did was called “Climbing as an Experience of Nature”. And it was something special, something that went beyond the normal slide shows. And that was in Hamburg, I think, at the America-house, a great showroom. And I was really proud of it, because not too long before that, I had seen a slide show by Reinhard Karl at exactly the same spot. And there were really 200 people there. And it was my first real presentation, in front of 200 people. And at the beginning, I really held my breath until I got into it. But it was so well received that I got booked a real tour through the Alpine Club. And then I traveled from city to city, so to speak. And then there was, I think, a payment of 200 German Marks. That was really a lot…

Jürgen: Per presentation?

Mathias: Yes, so it was a lot of money.

Jürgen: Wow. Man, you really made a lot of money.

Mathias: Yes, I did. And during that time, I really did two presentation tours, one through northern Germany and one through the Ruhr area. And I earned about 10,000 German Marks. I put that aside for a year and a half to fulfill my big dream of going to America…

Jürgen: Before we get to that, let me just say that it’s quite a difference between climbing the north face and presenting it in a slide show. Now you have to explain it pictorially, your language comes with it, you called it multivision. So you never had the feeling if you can actually do it?

Mathias: I think if you’re so passionate about something, you can actually do it.

Jürgen: Then you just dare to do it.

Mathias: For me, it’s like that, then I just dare to do it. I just give it a try. Sure, in the beginning I stuttered a bit, but then suddenly something clicks and you get into a kind of flow, and maybe the enthusiasm will also spread to the audience. And yes, then… you can also share something with people there. I also designed this presentation for non climbers, I also wanted non-climbers to enjoy it. That’s why I went from bouldering, to sport climbing, to ice climbing, to big walls in “Climbing as an Experience of Nature”. And then I also had a longing to climb on warm, sunny rock again after some ice-cold days on the north faces. So I just went on like that. I also explained the different techniques, from crack climbs to finger pockets, so that even non-climbers would understand the passion I had for climbing. And I also held those presentations during my civilian service for senior citizens at their retirement home. And they were thrilled because it came with passion… Sure, it certainly also plays a role that you can ignite something in people. But just explaining something…

Jürgen: Whatever you do passionately.

Mathias: Yes.

Jürgen: It’s easy then.

Mathias: But also mentally moving to a different level helps me in my professional life today. We haven’t talked about that yet. I’m still a passionate photographer, but I don’t earn my money from that anymore. I do IT support for everything that has to do with Apple. And people appreciate me because I can explain things in a way that someone who doesn’t understand the subject can understand. And they are very grateful for that.

Jürgen: Simply reduce the simple.

Mathias: Exactly. And not act as if the other person must know it already. Everyone starts out small. I also started out small, both with climbing and with photography, as well as in IT. So I know how stupid I was, how naive I was. And then I try to put myself at that level again… I don’t mean it with any disrespect, it’s just that I try to put myself in the other person’s shoes and see it from their perspective. And that’s how I explain it. That’s how I did it in the slide presentations. I think that’s why it was so well received.

Jürgen: But it’s also nice that you just went for it. When you are inspired by passion, you just start. That means that fears tend to take a back seat. I think the first presentation was probably still very exciting. But you did it anyway. Exactly, and as you mentioned, a lot of money came in and you were able to fulfill a dream, namely to travel to the USA.

Mathias: Yes. A funny anecdote about the presentations on the side: the presentation season is of course always in winter because it’s usually not that time of the year to climb outside. Back then, I only had a Passat Variant as a car. It was a very, very cold winter, with temperatures constantly around -10 or -15 degrees Celsius, and I traveled from city to city. They asked me, “Mr. Weck, would you like us to book a hotel for you?” And I knew that if I didn’t do that, I’d get a flat rate. I also camp out in winter for climbing and sleep in the car at freezing temperatures, so I didn’t mind for this trip either. Anyway, between all this equipment, I really had to squeeze myself in…

Jürgen: So that you get the flat rate and don’t have to invest the money in a hotel.

Mathias: Exactly. But it paid off in the end. It was so cold that even the coke bottle in the car froze.

Jürgen: Really?

Mathias: Yes. It was always hard. I can’t just sleep in the car every night without taking a bath for two or three weeks without washing myself. So I always went to the public indoor swimming pool in the morning and then had to put on my swimming trunks, which were frozen to ice from the day/night before, that meant jumping from the changing room into the showers really quick. (Laughter)

Jürgen: Okay, but then you were able to put the money aside.

Mathias: Exactly. Exactly.

Jürgen: How did it start in the USA?

Mathias: Yes, in the USA… there were of course several destinations. One was of course climbing-related. These were also dreams, awakened in many cases by books by Reinhard Karl. And…

Jürgen: Let’s stick with one of them. Of course, El Capitan is the goal of dreams, I think. If you’ve ever stood in front of it, it’s really crazy. And since you just mentioned Reinhard Karl, there’s something in that book that impressed me so much back then, “Kaum Zeit zum Atmen”, “The Point of No Return”. And you have “The Shield”, you climbed that tour.

Mathias: Exactly, yes. And it was… apart from the big walls in the Alps, which is a completely different game, where you somehow go from belay to belay and the other one climber follows by also climbing. And climbing a big wall, on El Capitan, is… very different, with a lot more of technical equipment, haulbags and so on.

Jürgen: So it’s a lot of technology, right? How do I follow up properly?

Mathias: Right, exactly. And… Yes, we didn’t know anything about those technics. With John and Todd, they were from Santa Barbara. I had met them somewhere… yes, in some other climbing area. They also wanted to do a big wall. And… yes, that’s when my little bit of megalomania came in again. I said, well, we don’t need to warm up. They wanted to do something easier first. But I said, come on, I have good experience with megalomania. We’ll do the big one right away.

Jürgen: Right away the right one.

Mathias: After that we’ll know how it goes. Yes, it was fun, everyone got their task to prepare. So, Todd took care of the food. Which in retrospect turned out not to be such a good idea, because he had just bought Salt Crackers and dry tortillas. We realized on the climb, that dry tortillas make excellent frisbees, because you couldn’t eat them, they were too dry. It’s a vertical desert. To anyone who wants to climb El Cap, I can only say, water, water, water. That’s the key and most important thing. And John had taken care of the topo. And the literature, as we found out later. Because halfway up, after we had already hauled up the haulbags to the Mammoth terraces, thats the strenuous part, that’s where it’s not yet vertical, where the fat things then grind on the granite

Jürgen: when you have to pull it up over rock.

Mathias: Yes, well, at the beginning we had it in theory, I had read it all nicely in the Reinhard Karl books too. You build yourself a kind of pulley. Just redirect the rope through the carabiner, then put in the jumar, stand in the jumar, and then you think…

Jürgen: I’ll just pull up.

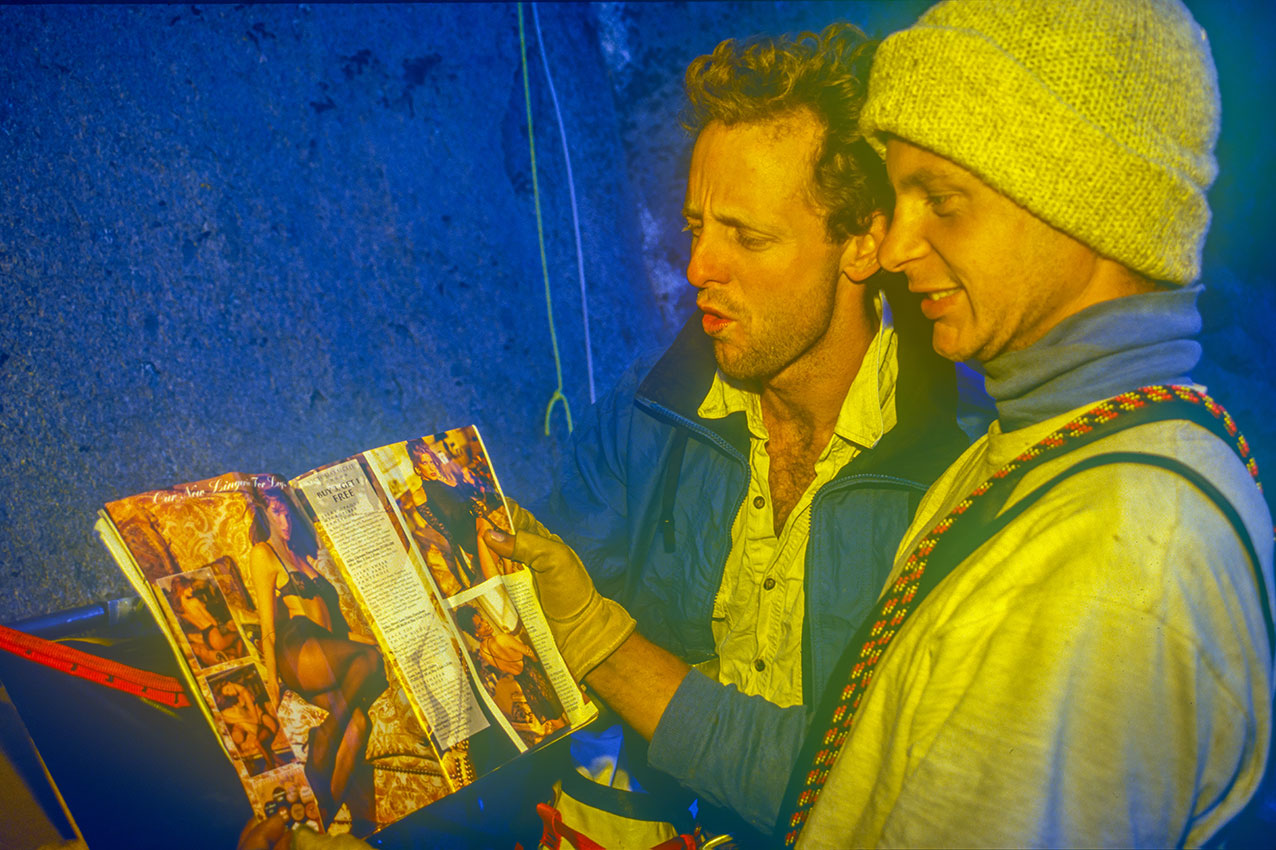

Mathias: The haul bag comes up. No, you have to actively brace yourself against it, your body weight won’t do anything. It’s such a terrible grind. Well, anyway, halfway through, I dug around in the haul bag and found a thick Victoria’s Secret catalog. (laughter) And that… that John had packed, it flew down the wall. Can’t be done anymore, but then we come back to the topic of fecal podcast here. (Laughter) Of course, the big question is how do I do the business? Nowadays you have to poop into a tube… do your business and then take it with you. And back then we were still allowed to poop into a paper bag and then catapult that paper bag down the wall. I still think it’s okay, because after a 500-meter flight, it just goes “pam” and paper and shit is just spread around in the forest, not much of it remains. And… but of course, if there are too many people around, at some point it won’t work anymore. But back then it was still common to do so. Yes, then… we had already done some very exciting pitches somehow. As I said, nobody knew how to do big wall climbing at the beginning. When you do aid climbing, you usually move from piton to piton, hammer the hooks in, right. Place your corded ladder and test the piton with jumping into the rope ladder a bit. You definitely shouldn’t do that with the first piton when you’re 10 meters above the ledge.

Jürgen: It can be very unpleasant, yes.

Mathias: John then did so, and he really did fall onto the ledge, it was a semi-smooth fall. But in any case, he didn’t feel like leading for a while, so I led most of the pitches into the headwall. Yes, and then at some point we were hanging below the so-called „Triple Cracks”. There were bolts there, well at least not bolts as you know them today, but those were these „Sticht“ bolts. You just make a tiny little hole with a hand drill bit…

Jürgen: They’re not even that far in either.

Mathias: They’re just about that far in.

Jürgen: Two or three centimeters, yes.

Mathias: I had set one of those myself once and knew that you can’t really trust them. There were a few more of them. And somehow I had attached all four Haul bags, each weighing about 40 kilograms, to one of those hooks. And I was already preparing a few more things. And suddenly I saw how the hook started to bend out slowly. Then I quickly spread the load a bit more. And then we all decided that we wouldn’t all hang up here, but rather spread out somehow. One guy down at the belay below and two guys up top. John was hanging further down, Todd and I had breakfast at the top and then lowered some Breakfast down bit by bit. And during breakfast, suddenly “Bang!” And Todd was suddenly hanging ten meters further down and the breakfast was at the base of the wall.

Jürgen: What happened?

Mathias: Yes, something with the porterledges, they were homemade porterledges. I also had a homemade one. That was…

Jürgen: Shall we say, porterledges, so to speak, a, let’s say, a rigid hammock, where you can hang yourself onto the wall.

Mathias: Exactly. We knew that hammocks are the most uncomfortable things ever. We had tried them before. You just hang in them like a sausage, yes. And a porterledge is just like a stretcher. And in this case, I had bought a porterledge from someone in Camp 4. It was homemade, but with cords on it to adjust it. It was very simple, but very light and very strong. And the other two guys just had a new self-made one. It was much heavier in weight. And it was sewn. And sewn is always, when you sew it yourself, not so clever, I guess. Anyway, a seam broke. That lost its balance. And then it came crashing down. Of course, you’re always roped up when you’re sleeping, in case something like that happens. But Todd cut his hand pretty badly then too. And, yes, then the next night, luckily, we had what’s called Chickenheadledge.

Jürgen: He had a normal space there.

Mathias: And, yes, that was also an adventurous experience. But the worst thing I remember is thirst. Thirst, thirst, thirst. It was pleasantly warm, long trousers, T-shirt. There was always a light, or so we thought, light wind, but around noon, so the wind just blew through these thermals that were also created on the mountain. And then a 50-meter rope just hung horizontally in the air. That’s how strong the wind is. It dries you out completely. You arrive at the belay and want to call down “on belay”. And you can’t talk at all. Because everything is glued together in your mouth. We had planned to… normally you do it like this: you start climbing, fix lines up to the Mammoth Terraces, which is more or less the middle of the wall, you fix some ropes, bring up all the haul bags, then rappel back down, take a two-day break in the valley and rest, then go up again and climb the rest. We didn’t do that. We got in and climbed it the classic way. But it took us five days. And 40 liters of water for three people for five days is just not enough.

Jürgen: Definitely not enough.

Mathias: You could have drunk two liters of water in one go.

Jürgen: Let me ask you something else, because you just said that the thing hangs horizontally for 50 meters. There is something very special in “The Shield”, this “point of no return”.

Mathias: Yes.

Jürgen: So when you go into the headwall, where it forms an overhang, there’s no going back, right? When you get in there, you have to go all the way.

Mathias: Exactly.

Jürgen: Whether there’s water or…

Mathias: Right.

Jürgen: How did you decide there? There were already things that went wrong, portaledges that crashed through.

Mathias: Fortunately, that only crashed through afterwards. We had to go up through that.

Jürgen: Okay. But was that really a point for you too, where you say, okay, now there’s a decision to make about going back down?

Mathias: Yes. We actually had a short discussion about it. On the first day, we made it up to Mammoth Terraces. That was good, but we were completely wiped out. And on the second day, we just… I think that’s when we… We really only made it into the headwall.

Jürgen: You also slow down considerably there.

Mathias: We were so slow. I think it’s four pitches to the headwall from Mammoth Terraces. It was this really big roof, and we were like, “Do we keep going or shall we go back?” Then we said, “Come on, let’s keep going.” And that’s when… since there were three of us, it was really adventurous for the third one… Well, the second and third do not climb, they jumar up the rope. For the first one to jumar is still ok, he still has the pitons in and is always right close to the wall. But the third one, he then only has the rope free hanging up to the next belay. He then has to swing out.

Jürgen: He swings out.

Mathias: He swings out 20 meters completely into the open air. And from that on, that’s clear, you can’t rappel anymore, you can’t get down the wall anymore, you’d have to climb back down the whole thing or better get up. It’s the same with rescue attempts. As soon as people have to be taken out of the headwall, the rescue team comes in from above, uses very long ropes and clips into pitons to stay close to the wall.

Jürgen: To get closer to the wall.

Mathias: To get closer to the wall, because otherwise you can’t get down.

Jürgen: Okay, wow. But you got through it well.

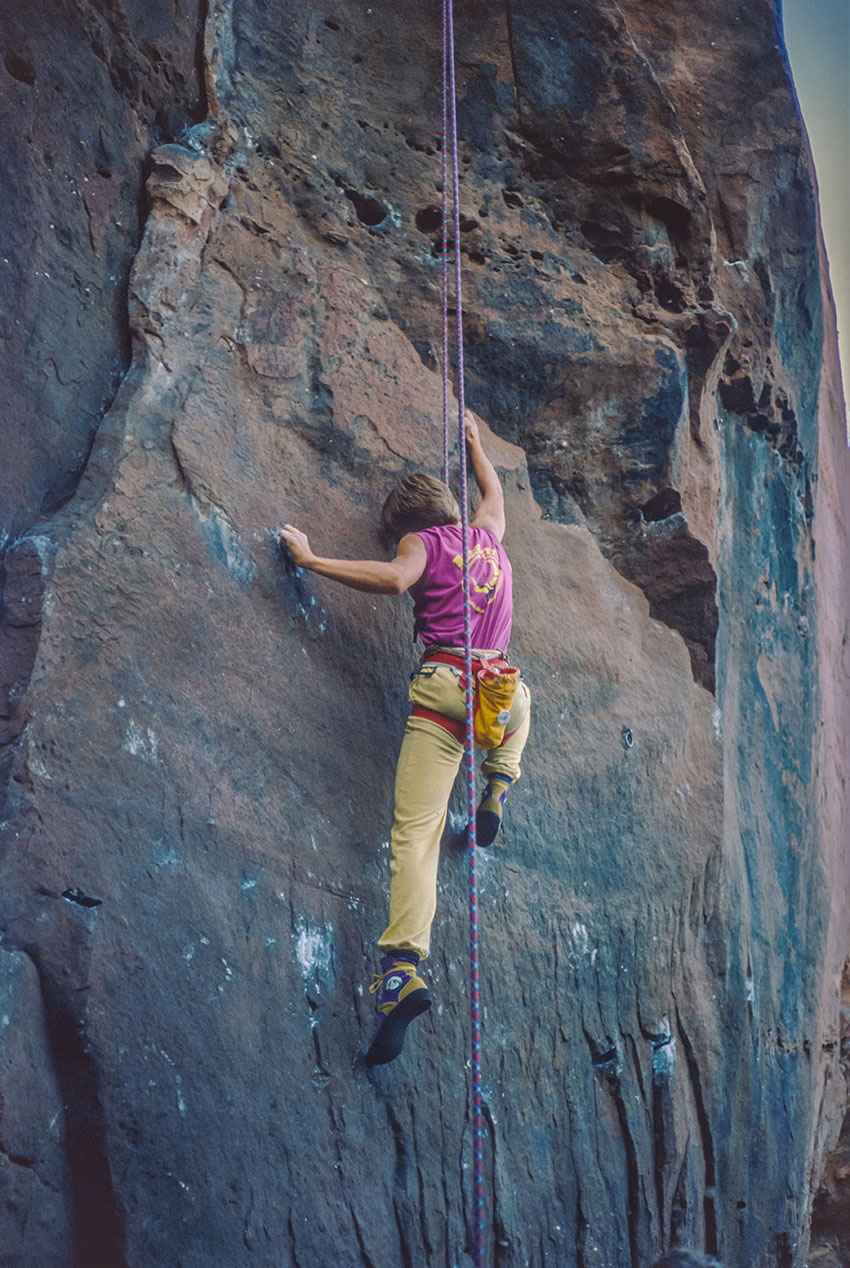

Mathias: We got through it and, yes, had another experience. Another story that was stuck in our heads before. Like all the other things, just like that. The three north faces and also the big wall, I just wanted to have done that somehow. I didn’t do it again afterwards. I proved to myself that I could do it. I could have done it again. But the Shield was one of the harder big walls anyway. I didn’t have to do something similar again. I also brought back some really good pictures. I actually had the complete Hasselblad equipment, a 6×6 camera, with me. It was a huge photo backpack. 35mm film equipment too. These triple cracks, as they’re called, are three hairline cracks offset parallel to each other. You then nail your way through them with so-called “Rurps”. It’s like a razor-sharp blade that you hammer in. It’s, yes, they are just about a centimeter.

Jürgen: That’s the only way to go. Because these pitons were developed to fit into these thin cracks.

Mathias: I climbed up that pitch, attached myself at the belay, pulled the camera equipment up. And then the guys below at the last belay pulled off the rope. And Todd lead that pitch again, just for the photos. You don’t normally do that on a wall like that, to lead the crux pitches a second time just to get photos. But I didn’t regret it, because the shots, of course, they turned out nice and are a great memmory.

Jürgen: Yes, amazing. Okay, that of course also explains why it took five days. Yes, well that was just a snippet. I think there was still a lot in the US. You climbed “Separate Reality”, a lot more. But that’s it for now from the US. But you just mentioned it with the… Yes, you did it once, and then somehow you don’t have to do it again, even after the three north faces, when you achieve such goals, Mathias. So what is it like to achieve a goal like that? Does it sometimes create an inner void? Or do you say, oh, I have to have the next goal right away, I have to move on?

Mathias: Well, you’re touching on a topic that I think many extreme climbers go through when they’ve worked hard for a long time to achieve a goal. Then you actually do fall into a kind of hole afterwards. And it was always really hard for me when I’d done a wall with someone and it was a purely functional partnership, where there was no real friendship, and then you were alone after that wall too.

Jürgen: That affects the togetherness, the feeling of having achieved something together.

Mathias: Exactly, then you have… If you don’t have anyone to share these experiences with, it’s really difficult. And after these three north faces, Eiger, Matterhorn and Walker, it was like that, I thought, come on, next summer it has to continue. So, for me, the Freney Pillar on Mont Blanc would have been due somehow, that was planned. I then set off with someone, we had been to Mont Blanc du Tacule to do a couloir and camped up there in the Valle Blanche. We did that couloir and said, I don’t feel like this ice and snow shit anymore. Luckily my buddy agreed, and then we decided to leave Chamonix. We went to Verdon and I remember we climbed the first few routes with a walkman on top rope. Just sun and rock.

Jürgen: Just having fun, so to speak.

Mathias: Exactly, and that’s actually always been the case for me. So, when I have a personal goal that I’ve been working towards for a while, when I achieve it, then it’s done, I don’t necessarily have to repeat it again, keep repeating it. That’s… well, for me it’s that it also gets a bit boring. Well, it’s different with sport climbing, but we might get to that later.

Jürgen: We’ll get to that, exactly. Thanks for the insight, but you did one more special thing. Norway is now also very big in sport climbing because of the Hans-Hellerin-Cave. And you were also in Norway. And I hope I’m pronouncing it right, at Hägefjell.

Mathias: Right.

Jürgen: Yes? And there is a route there that I think you did with someone special. “Even cowgirls get the blues,” a 500-meter wall. What is Hägefjell like?